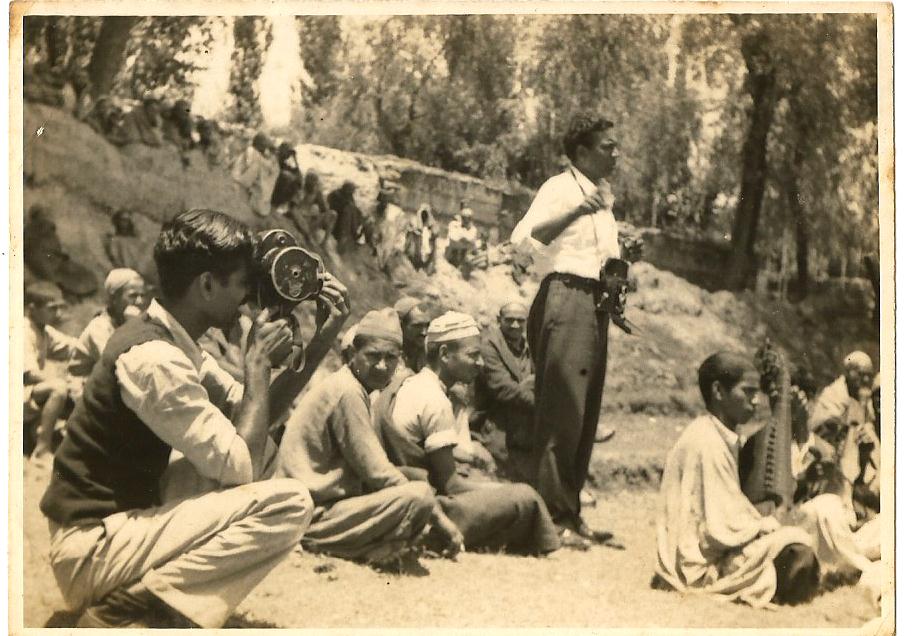

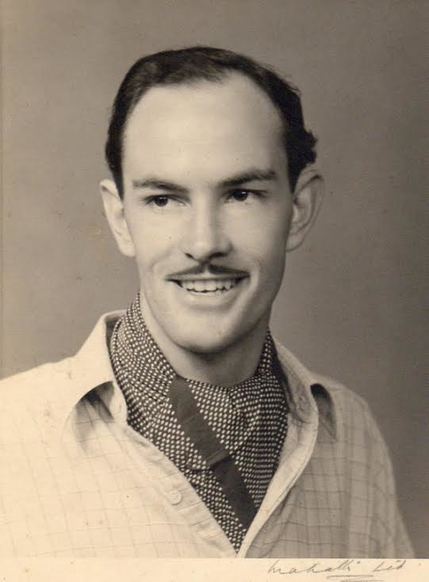

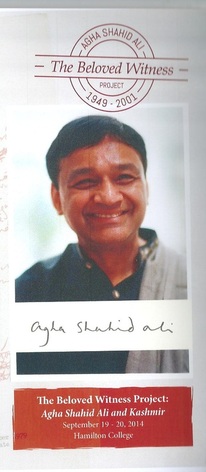

With the help and permission of Garga's widow, Donnabelle Garga, I am able to post some wonderful images both from the film and taken at the time it was being made and to share a little more about this historic documentary. Garga was a leftist and his take on Kashmir reflected a progressive mindset, which in the late 1940s was sympathetic to Sheikh Abdullah, the leader of the main Kashmiri political party, the radical and nationalist National Conference.

In an article entitled Fragments of a Life, Garga wrote about how 'Storm over Kashmir' came to be made:

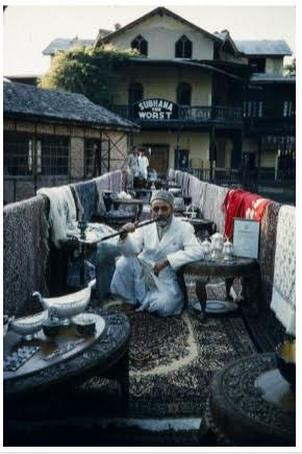

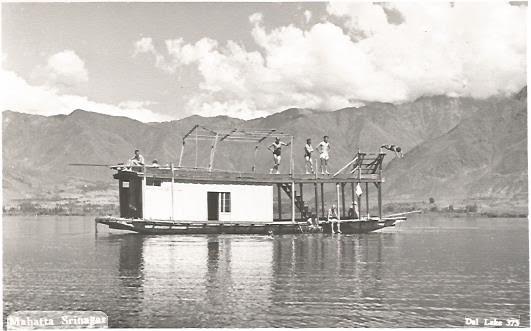

'Soon after the traumatic experience of partition, I found myself in Kashmir exploring the possibility of making a documentary film (eventually titled Storm over Kashmir) on the political situation there. K.A. Abbas, who was already in Srinagar at the invitation of Sheikh Abdullah, invited me to stay with him in his large, lovely houseboat. This was the beginning of a long friendship and collaboration on ‘various adventures and misadventures’ as he put it. Kashmir in 1948 was a most exciting place to be in. Raiders from across the border had overrun the valley, pillaging and killing innocent people. They did not even spare the nuns and burnt a chapel. There was widespread anger and revulsion against the marauders and their atrocities. Journalists and photographers from all over the world had converged on Srinagar. Our houseboat was a sort of ‘Press Club’ where everybody met and discussed the day’s happenings. Among the other visitors, I particularly remember the late D.P.Dhar, a firebrand, who would arrive with a rifle slung across his shoulder.

It was here I met the legendary French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Many a time he would invite me to join his photographic expeditions. He created all those incredible masterpieces with a battered old Leica, without filters or any artificial light. He told me that he had started his career with Jean Renoir and then switched over to Photography. Cartier-Bresson introduced me to a man to whom I owe much: Georges Sadoul'

The late Dileep Padgaonkar also wrote about the film in his foreword to Garga's 2005 book, The Art of Cinema: an insider's journey through 50 years of film history:

Around this time, Gandhi was assassinated in Delhi and Garga had to hasten to the capital to ensure the safety of his parents who lived there after partition. He had no project in hand. One day, BalwantGargi, the Lahore friend who had prodded him to take up cinema as a career informed him that Sheikh Abdullah, the chief minister of Jammu & Kashmir had invited writers and artists to visit the state which had been invaded by raiders from Pakistan. The two decided to approach Abdullah for help to make a documentary.

The Kashmiri leader told them bluntly that he had no funds for the project. All he could do was to place a houseboat at their disposal and look after the transportation. With great difficulty they managed to get a camera and raw stock which was still in short supply. The writer Rajinder Singh Bedi suggested the plot.

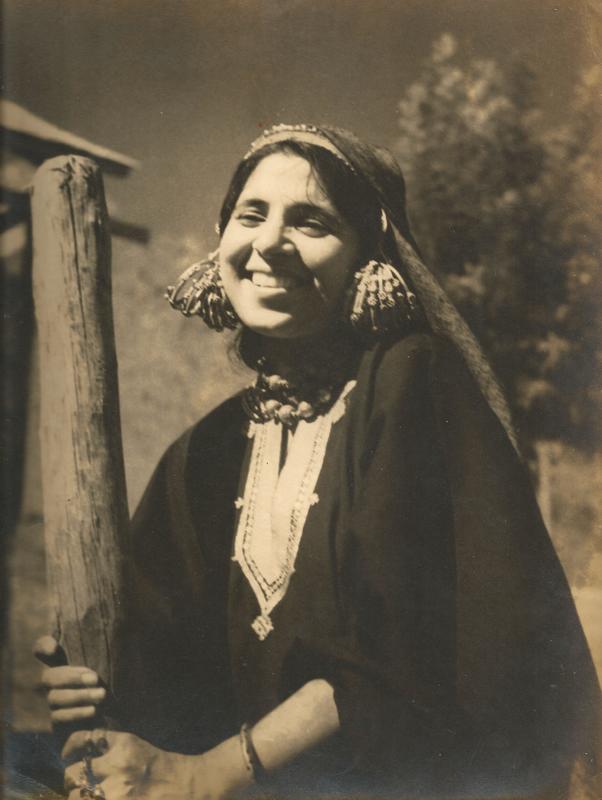

Te main character was a woman who had been raped. Her husband had been killed and her house destroyed. A young girl from Delhi, AchalaSachdev, was given the role. This was the first time she faced the camera. The unit began work in Baramullah where atrocities had taken place. Nuns had been molested in a church and the chapel had been ransacked.

Garga felt at home in Kashmir for in his childhood and early youth he camped there every summer. He would take the ‘Nanda Bus Service’ which ferried passengers between Lahore and Srinagar. (Today, the Nandas rank among the leading industrialists of India.) The familiarity with Kashmir proved useful during the making of the documentary and so did the company of several people Garga met including the French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, the American journalist, John Gunther, and budding Kashmiri politicians like Shamlal Watt and D.P.Dhar. The latter always went around armed with a rifle. Also present was K.A.Abbas whose houseboat served as a veritable Press Club.

The film was called Storm over Kashmir. Abbas had suggested the title after watching the rushes. RomeshThapar, a down-and-out editor of a communist publication, wrote the commentary and narrated it. Sardar Malik, who had been active in the pro-communist Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) and had done musical scores for Uday Shankar’s academy composed the music.

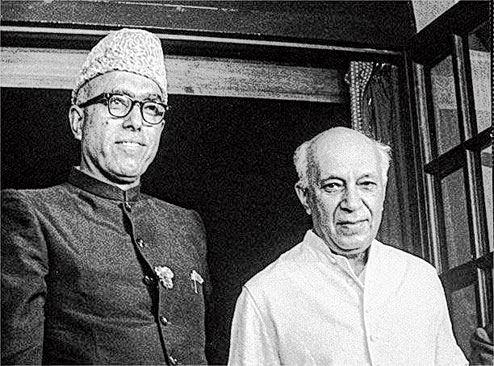

Though the Congress President, PattabhiSitaramayya, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and several foreign correspondents had seen and appreciated the documentary, the censors would not pass it on the grounds that it did not show the Indian army defending Kashmir and that it depicted Sheikh Abdullah in a flattering light. Garga travelled to the front, befriended General Thimayya, then in charge of the Kashmir operations, shot images of soldiers as well as of a procession of children shouting” ‘Beware, you raiders. We Kashmiris are ready to face you.’ Four decades later a man came to meet Garga and told him that he was one of those children marching past his camera.

The censors finally cleared the film and it went on to win critical acclaim in prestigious publications like Indian Documentary which featured it on its cover page. But it was never released in India. Until 1988 the Famous Cine Laboratory in Tardeo, Bombay, reportedly had a print in its possession. Garga reckons that it may have found its way to the National Film Archive in Pune.

The most authoritative account of 'Storm over Kashmir is in Meenu Gaur's SOAS doctoral thesis entitled 'Kashmir on Screen: region religion and secularism in Hindi cinema'.

The Progressive legacy in Kashmir is brought out well by the film Kashmir Toofan Mei, or Storm Over Kashmir, made in 1949 by a group of theatre actors and filmmakers closely allied with PWA and IPT A. Storm Over Kashmir is produced by

India Art Theatres Ltd and directed by BD Garga, well-known film academic and

author of several books on Indian cinema. Keeping with Progressive traditions, the film introduces 'the people of Kashmir' in the star cast along with IPTA artists. The IPTA actress, Achla Sachdev plays the main protagonist of the film, and the commentary for the film is credited to the Progressive writer, Rajinder Singh Bedi.

The title of the film is reminiscent of Pudovkin's 'Storm over Asia' (1928), considered one of Soviet cinema's silent film classics. While Storm Over Kashmir is described as a documentary, most parts of the film are fictionalized, meant to function as a generic and not specific narrative of what ordinary Kashmiris endured during the tribal raid.

The film reveals to us the horrors of the tribal raid through the character of a

Kashmiri woman, Shabbo. The film opens with Shabbo mourning the death of her

infant, sitting amidst ruins and the destruction wrought at the hands of the tribesmen.

The commentary informs the audience, 'Death and destruction, hate and fear, these

were the gifts of raiders from Pakistan brought to the people of Kashmir'. The film then goes into flashback painting a portrait of an idyllic village life in Kashmir. The

commentary in the film highlights the struggles of the Kashmiri workers and peasantry, and eulogizes Sheikh Abdullah as a revolutionary leader:

Sheikh saheb's arrival sent a thrill through the village ... there was an air of

expectancy. A movement was being launched demanding a popular government

and economic reforms for the peasants .... Sitting in the cool shade of the

Cyprus trees, she had heard her revered leader tell them that they must win the

power with which to build a new life, that they must never despair, that victory

would ultimately be theirs. The peasants of the Kashmir valley had suffered

much and at times it looked as if their fate would never change. With Sher-i-

Kashmir amongst them their determination grew to end the rotten state of affairs

in their land ... .

This idyllic village life is disrupted with the attack of the tribesmen. Scenes of plunder follow, and the entire village is razed to the ground. This is followed by documentary National Conference voluntary militia, portraying the resistance offered

to the tribesmen by the people of Kashmir. Images of workers, the children's army ('Bal Sena') and the women's militia, marching and carrying banners, 'Shahidani Kashmir Zindabad ['Long Live the martyrs of Kashmir'] - Silk Weaving Factory Workers Union, Raj Bagh', and 'We will defend our motherland with our young blood- Bal Sena', are inter-cut with images of Sheikh Abdullah paying his respects to the 'martyrs'. The commentary speaks of hope and freedom in the framework of socialism as images of Abdullah and Nehru roll on the screen:

The Kashmir of tomorrow is taking shape today. Men, women and children all

of them have a part to play. The masses of Kashmir have found their soul. Bent

backs are no longer bent, eyes doused by poverty are aglow. The old hates have

dissolved. A new comradeship had evolved between worker, peasant, and

intellectual. Freedom has begun to find its roots. Yes, a new Kashmir is rising

from the rubble heaps. It is the Kashmir ofShabbo's dreams. Her son is dead but

there are millions of other sons of Kashmir who will defend their new won

freedom, till their fertile field, and finally reap the rich harvest. An ugly chapter

has ended. A new age has begun.

The question of the conditional and contested accession of Kashmir to India is not

represented in this film, and instead, Kashmir's past and present are intrinsically woven with the future of a socialist India.

Donnabelle Garga has also sent some wonderful photos of Achala Sachdev (1920-2012) in 'Storm over Kashmir'. Her film career continued until 1995, when she played Kajol's grandmother in 'Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge'.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed