Kashmir Journal: 'Khayalon ki Ladai' (Clash of Ideas)

In an occasional series for KashmirConnected, the eminent historian of Kashmir Chitralekha Zutshi writes about her experiences across the Valley and the manner in which the past moulds Kashmir's present

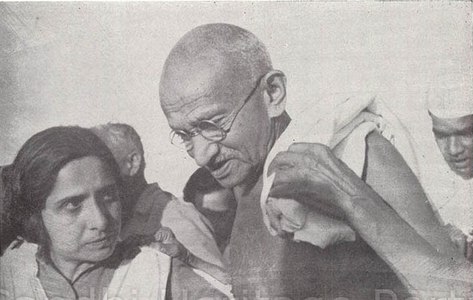

Mridula Sarabhai with Gandhi in Bihar: Gandhi Heritage Portal

Mridula Sarabhai with Gandhi in Bihar: Gandhi Heritage Portal

Writing in the 1950s, Mridula Sarabhai described the situation in Kashmir and its relationship to India as a ‘khayalon ki ladai' (clash of ideas). A Gandhian activist who had been deeply involved in Kashmir affairs since the 1940s, Sarabhai grew increasingly alarmed at the growing gulf between Kashmir and India, as well as between Kashmiris and Indians, in the 1950s, in particular after the arrest of Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah in 1953. She recognized that the khayalon ki ladai created and reinforced multiple lines of division (which can be described today as ongoing states of partition)—between India and Pakistan, between Kashmir and India, between Pakistan and Kashmir, between Jammu and the Kashmir Valley, and between the Kashmir Valley and Ladakh. She repeatedly pointed out that ‘vested interests’ used the media and other avenues to promote their own ideas, which often circulated in the form of rumor, with the ultimate objective of driving a wedge between these multiple players so as to keep the conflict simmering and eventually forcing Kashmiris into the arms of Pakistan.

Several decades have passed since, but the khayalon ki ladai rages on, and if anything, has become even more vehement. At a very basic level, the events this past month at the National Institute of Technology, Srinagar, and at Handwara, are a result of the as yet unresolved relationship between Kashmir and India, between the state and center, and between the two nationalisms. Sarabhai, Balraj Puri, J.P. Narayan, and many others like them, incessantly implored the Indian government to stem the rot within Kashmir and its institutions in the 1950s, 60s, and into the 70s, and to take concrete steps to bring Kashmir into the national, democratic mainstream so as not to allow a victory for the opportunists. Their words went unheeded. So strong was the fear that Kashmir would dissociate from India that the Indian government supported a series of dictatorial, corrupt, and ineffectual governments in the state—including the first National Conference government—which promised them Kashmiri loyalty. In the process, they drove Kashmiris towards the very enemy they were attempting to lure them away from.

When young Kashmiris shout pro-Pakistan and anti-India slogans at cricket matches and other events, it is not necessarily because they believe that Pakistan is a better option, or because they have fallen prey to radical Islamic ideologies, but rather because they do not feel and have never felt included in India and its rhetoric of democracy, secularism, and globalization. This is especially true of this generation, which grew up during the insurgency and India’s military response to it, an experience which they view as akin to living under an occupation. Those who leave for other parts of India to seek a better life have often been met with hostility and suspicion. Kashmiris inside and outside Kashmir are labelled anti-national traitors even before they have a chance to decide what they feel. Since they have not been treated as equal citizens, they feel no loyalty towards India.

Kashmiri nationalism, now articulated as a demand for aazadi (freedom), has become irreconcilable with mainstream Indian nationalism. Even if the rampant mis-governance, a major Kashmiri grievance, were to be addressed now, it may not be enough to dampen the political aspiration for aazadi among the younger generation of Kashmiris. These young men and women have to be given a stake in democracy, an idea they do not believe in because they have never felt represented by their political leaders, at least not the elected ones. In such an atmosphere, where the memory of historical wrongs merges with present injustices that are stoked in the media and by political leaders, aazadi takes on a powerful resonance.

When young Kashmiris shout pro-Pakistan and anti-India slogans at cricket matches and other events, it is not necessarily because they believe that Pakistan is a better option, or because they have fallen prey to radical Islamic ideologies, but rather because they do not feel and have never felt included in India and its rhetoric of democracy, secularism, and globalization. This is especially true of this generation, which grew up during the insurgency and India’s military response to it, an experience which they view as akin to living under an occupation. Those who leave for other parts of India to seek a better life have often been met with hostility and suspicion. Kashmiris inside and outside Kashmir are labelled anti-national traitors even before they have a chance to decide what they feel. Since they have not been treated as equal citizens, they feel no loyalty towards India.

Kashmiri nationalism, now articulated as a demand for aazadi (freedom), has become irreconcilable with mainstream Indian nationalism. Even if the rampant mis-governance, a major Kashmiri grievance, were to be addressed now, it may not be enough to dampen the political aspiration for aazadi among the younger generation of Kashmiris. These young men and women have to be given a stake in democracy, an idea they do not believe in because they have never felt represented by their political leaders, at least not the elected ones. In such an atmosphere, where the memory of historical wrongs merges with present injustices that are stoked in the media and by political leaders, aazadi takes on a powerful resonance.

The alienation between Kashmir and India is evident in the events at Handwara, where a rumor that a young girl had been sexually molested by a soldier led to widespread street protests, the destruction of an army bunker, army firing in response, and the deaths of several innocent Kashmiris. Rumors have historically played a powerful role in Kashmiri politics—fueling demonstrations and clashes with authorities—and an allegation such as this one in particular has the potential to erupt into a high level of violence because it evokes memories of the loss of dignity that Kashmiris have had to suffer at the hands of the military forces for over two decades. The mistrust deepens and violence spirals further out of control as the media ratchets up tensions and authorities mishandle the investigations into such incidents, creating a feeling amongst Kashmiris that they have no recourse to justice, especially through political institutions.

It is no surprise that the recent disturbances emerged in the context of the new government that has taken charge in the state. A coalition between the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) reminds Kashmiris of the repeated collusions between the state and the center to squelch their political aspirations. Furthermore, after the death of Mufti Muhammad Sayeed, the ability of the PDP to represent Kashmiri interests by keeping the BJP from asserting its agenda in the coalition is considered questionable (and is one of the reasons that it took several months for the new coalition to be formed).

Equally significantly, the coalition, and the 2014 legislative assembly election that gave birth to it, has institutionalized the lines of division between Jammu and the Kashmir Valley; while the former emerged firmly as pro-BJP, pro-India territory, the latter emerged as pro-state, pro-Kashmiri Muslim territory, represented until recently by the PDP. At present, disillusionment with the PDP is widespread, particularly in its South Kashmir constituencies, where the development aid and flood relief that were promised to the people by the PDP have not been delivered. The Jammu/Kashmir divide has been apparent in the wake of the NIT incident, with the Kashmir Valley tilting strongly in favor of Kashmiri students, while Jammu became a hub for those protesting on behalf of non-Kashmiri students.

NIT and Handwara are the symptoms of a much deeper malaise that cannot be treated by the band-aid measures being proposed in the wake of these crises. To restore a sense of confidence among Kashmiris, there is a need to take courageous, long-term action to tackle the problem as whole when Kashmir is relatively peaceful, rather than stepping in with quick-fix and temporary solutions when a crisis seems to get out of hand. Such solutions merely paper over the khayalon ki ladai, which continues to be exploited by various elements and carries on unabated. After all, even though the lines of division and the ideas that create these fissures have shifted somewhat since the 1950s—when Sarabhai lamented and warned of the deteriorating relationship between Kashmir and India—the battlefield remains very much the same.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in Scroll in

Chitralekha Zutshi, first posted May 2016

do read the other episodes in Chitralekha Zutshi's Kashmir Journal