Kashmir Journal: the majesty of Kashmiri shawls

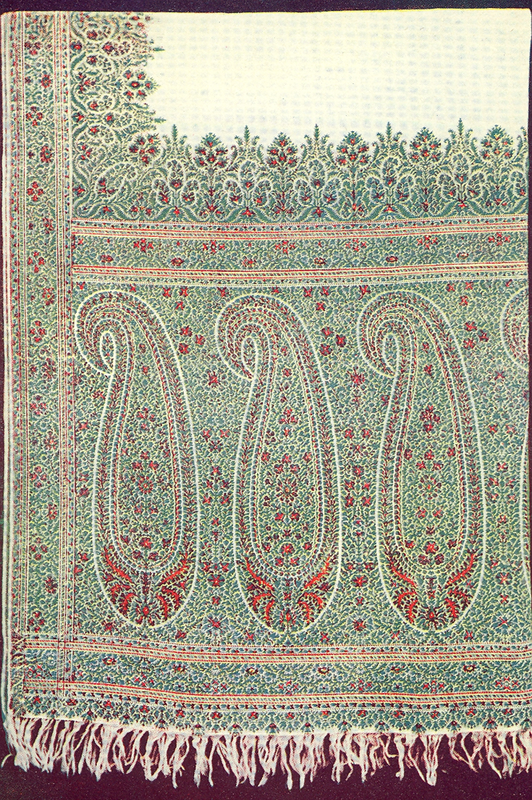

If there is a single commodity that has over the centuries represented the beauty of Kashmir across the world, it is the Kashmiri shawl. The fineness, warmth, delicacy, and stunning designs of these products have been celebrated in historical, fictional, political, and design narratives in multiple languages, including Persian, English, and French. Through their trade across the Indo-Persian world starting in the sixteenth century, and later Europe and America through the course of the nineteenth century, Kashmiri shawls have served as far more than merely items of commerce; indeed, apart from being coveted articles of clothing, they have been prized objects of gift exchange between political entities, required elements of a woman’s trousseau, status-symbols, and representations of a land on the far edges of empire, the natural splendor of which endowed its artisans with inherent artistic abilities to produce such fine textiles.

The late-nineteenth-century Persian history of Kashmir, Tarikh-i-Hassan, attributes the origin of the production of shawls in Kashmir to the introduction of shawl wool, pashmina, to Kashmir by the renowned Sufi mystic, Sayyid Ali Hamadani, also credited with spreading Islam in Kashmir. According to Hassan, on his travels through Ladakh and Turkistan, Hamadani came across this fine wool, and brought it with him to Kashmir in the late fourteenth century, convincing the Sultan not just to adhere to the proper strictures of Islam, but also to have the fine wool woven into shawls and other articles of clothing.

While for Hassan, thus, shawls were closely tied to Kashmir’s very transition to Islam, for late-nineteenth-century Victorian narratives, the Kashmiri shawl (and through it Kashmir itself) was a perfect symbol of the Orientalized East—pre-industrial, close to nature, and at the same time matchless in elegance and grace. As one such article declared, Kashmiri shawls were an “immutable article of dress,” that were “designed for eternity in the unchanging East,” and “woven by fatalists."

While for Hassan, thus, shawls were closely tied to Kashmir’s very transition to Islam, for late-nineteenth-century Victorian narratives, the Kashmiri shawl (and through it Kashmir itself) was a perfect symbol of the Orientalized East—pre-industrial, close to nature, and at the same time matchless in elegance and grace. As one such article declared, Kashmiri shawls were an “immutable article of dress,” that were “designed for eternity in the unchanging East,” and “woven by fatalists."

Empress Josephine of France in a shawl-dress with a shawl draped around her waist and shoulder, c1809

Empress Josephine of France in a shawl-dress with a shawl draped around her waist and shoulder, c1809

In reality, Kashmiri shawls were (and continue to be) the products of a complex and continually changing system of production and trade that involved both men and women, and was deeply connected to the political economy of the region and beyond. Spinners, weavers, dyers, washers, and embroiderers participated in an intricate process of manufacture, with small and medium traders and large factory owners trading shawl wool and the completed products internally and across continents. Before it could be traded, however, each shawl had to be branded at the government’s shawl department, since the state collected thousands of rupees in annual revenue on these exquisite articles. While the traders, particularly shawl factory owners, lived like kings, the spinners and weavers toiled in pitiable conditions, and Kashmir’s history is strewn with workers’ uprisings aimed at improving working conditions and pay.

Kashmiri shawl factory owners frequently revisited and revised shawl designs depending on the demands of the market—the size of the shawls became wider, narrower, longer, shorter, even as their colors and patterns responded to changing fashions in dress around the world. Srinagar hummed with the activities of Armenian, French, Sikh, and British shawl agents vying with each other to order the production of the finest Kashmiri shawl.By the middle of the nineteenth century, shawl designs were being copied and transformed into imitation shawls for the burgeoning European middle class in the British textile towns of Norwich and Paisley and the French cities of Paris and Lyon, as cheaper alternatives to the exorbitantly priced shawls from Kashmir. Inexpensive substitutes for middle-class Indians were also being produced in the Punjabi towns of Jullundar and Amritsar, where most of the so-called “pashmina” stoles and shawls are still manufactured.

Kashmiri shawl factory owners frequently revisited and revised shawl designs depending on the demands of the market—the size of the shawls became wider, narrower, longer, shorter, even as their colors and patterns responded to changing fashions in dress around the world. Srinagar hummed with the activities of Armenian, French, Sikh, and British shawl agents vying with each other to order the production of the finest Kashmiri shawl.By the middle of the nineteenth century, shawl designs were being copied and transformed into imitation shawls for the burgeoning European middle class in the British textile towns of Norwich and Paisley and the French cities of Paris and Lyon, as cheaper alternatives to the exorbitantly priced shawls from Kashmir. Inexpensive substitutes for middle-class Indians were also being produced in the Punjabi towns of Jullundar and Amritsar, where most of the so-called “pashmina” stoles and shawls are still manufactured.

The production, trade, and consumption of shawls thus linked Xinjiang, Lhasa, Yarkhand, Khotan—from where came the finest shawl wool, pashmina and tus—and Kashmir—where the shawls were manufactured—to Punjab, Persia, the Ottoman Empire, and Russia, and later England, Scotland, France, and even New York and Philadelphia—where shawls were consumed and their imitations produced. As shoulder mantles, waist girdles, turbans and robes for men, and scarves, shawls and dresses for women, Kashmiri shawls (and their imitations) had become essential elements of an elite as well as middle-class wardrobe by the late nineteenth century.

But what did/do Kashmiri shawls mean for Kashmiris themselves? For those involved in their manufacture and trade, they were a source of either a paltry livelihood, or a fairly good living, or indeed a rather luxurious one, depending on where along the production and circulation spectrum one was located and the size of one’s enterprise. Some shawls traders and factory owners were deeply involved in the political affairs of Kashmir in the latter half of the nineteenth century since they controlled not just vast wealth, but also urban sacred spaces such as shrines.

For as long as I can remember, a Kashmiri shawl trader visited us every winter throughout my childhood in whatever city in India we happened to live. My parents and grandparents would sit with him as he sipped his tea and regaled them with the latest happenings in Kashmir, thus keeping them connected to their homeland. His visits stopped for a few years during the height of the insurgency, which almost completely wiped out his business, but it revived. He still visits my parents every winter, displaying his latest wares, including shawls, embroidered saris and other dress materials, and variously-sized stoles, which are now in vogue.

He laments the decline in the shawl trade both within and outside Kashmir. In Kashmir, the art of weaving and embroidering shawls is dying out as young men move to other, more lucrative professions. Outside Kashmir, sales of shawls have plummeted in the recent past as new fashions move away from shawls and saris towards scarves and stoles. Most people are unwilling to spend the high prices for a real pashmina or jamawar shawl and would rather purchase the fake “pashminas” that now litter marketplaces around the world. Even the elites are no longer buying Kashmiri shawls as they did in the past.

Shawls, however, hold a much deeper personal and cultural meaning for Kashmiris that goes far beyond their economic value. When I was teenager, my paternal grandmother decided that she was going to spin shawl wool into yarn with her own hands, which she would then have woven into Kashmiri shawls for each of her granddaughters. She lived with us for much of the time she spent making yarn from the softest pashmina wool that my maternal uncle, then posted in Leh, brought for her. Thus began the laborious process of first cleaning the wool—by immersing it in rice flour and then separating the impure hairs from the pashmina—followed by hours at the wheel spinning it into the finest yarn. The balls of yarn were then taken by the shawl trader to Kashmir, where he had them woven into gorgeous shawls, embroidered with designs according to my grandmother’s specifications.

For as long as I can remember, a Kashmiri shawl trader visited us every winter throughout my childhood in whatever city in India we happened to live. My parents and grandparents would sit with him as he sipped his tea and regaled them with the latest happenings in Kashmir, thus keeping them connected to their homeland. His visits stopped for a few years during the height of the insurgency, which almost completely wiped out his business, but it revived. He still visits my parents every winter, displaying his latest wares, including shawls, embroidered saris and other dress materials, and variously-sized stoles, which are now in vogue.

He laments the decline in the shawl trade both within and outside Kashmir. In Kashmir, the art of weaving and embroidering shawls is dying out as young men move to other, more lucrative professions. Outside Kashmir, sales of shawls have plummeted in the recent past as new fashions move away from shawls and saris towards scarves and stoles. Most people are unwilling to spend the high prices for a real pashmina or jamawar shawl and would rather purchase the fake “pashminas” that now litter marketplaces around the world. Even the elites are no longer buying Kashmiri shawls as they did in the past.

Shawls, however, hold a much deeper personal and cultural meaning for Kashmiris that goes far beyond their economic value. When I was teenager, my paternal grandmother decided that she was going to spin shawl wool into yarn with her own hands, which she would then have woven into Kashmiri shawls for each of her granddaughters. She lived with us for much of the time she spent making yarn from the softest pashmina wool that my maternal uncle, then posted in Leh, brought for her. Thus began the laborious process of first cleaning the wool—by immersing it in rice flour and then separating the impure hairs from the pashmina—followed by hours at the wheel spinning it into the finest yarn. The balls of yarn were then taken by the shawl trader to Kashmir, where he had them woven into gorgeous shawls, embroidered with designs according to my grandmother’s specifications.

I was in college by the time I received my grandmother’s shawl, and since then I have been gifted several shawls, some new, but most belonging to our ancestors, passed down through generations within the two sides of my family, in the process cementing an entire web of relationships. Kashmiri shawls are tokens of commemoration and gifts of love deeply associated with the land—given to a bride by her adoring parents, a grandmother to her granddaughters, or a lover to her beloved. A popular Kashmiri folk song captures this beautifully:

Take me, take me, O Boatman to your bank,

O here flows the Jhelum, the deep river of Love.

My boat takes only the pair in love,

O here flows the Jhelum, deep river of love.

Shawl wool shall I spin with my own hands,

And shall get it dyed in saffron color.

An exquisite shawl shall I weave with my own hands,

And shall get it dyed in saffron color.

How soft—O how soft, is the shawl wool,

A song of its softness, I’ll sing.

O, the shawl wool is a heavenly thing,

A song of its softness, I’ll sing.

My mate’s head is crowned with a shawl-wool turban,

On his person looks lovely the shawl-wool pheran.

On my home loom was woven the cloth of turban and pheran,

A song of its softness, I'll sing ....

O here flows the Jhelum, the deep river of Love.

My boat takes only the pair in love,

O here flows the Jhelum, deep river of love.

Shawl wool shall I spin with my own hands,

And shall get it dyed in saffron color.

An exquisite shawl shall I weave with my own hands,

And shall get it dyed in saffron color.

How soft—O how soft, is the shawl wool,

A song of its softness, I’ll sing.

O, the shawl wool is a heavenly thing,

A song of its softness, I’ll sing.

My mate’s head is crowned with a shawl-wool turban,

On his person looks lovely the shawl-wool pheran.

On my home loom was woven the cloth of turban and pheran,

A song of its softness, I'll sing ....

Chitralekha Zutshi, first posted February 2016

do read the other episodes in Chitralekha Zutshi's Kashmir Journal