Kashmir Journal: Kashmiri and the languages of Kashmir

In an occasional series for KashmirConnected, the eminent historian of Kashmir Chitralekha Zutshi writes about her experiences across the Valley and the manner in which the past moulds Kashmir's present

It might seem odd that I have chosen to write about Kashmiri languages when Kashmir is in the throes of the latest round of raging unrest against the Indian state, but language is, in fact, tied deeply to Kashmiri identity and Kashmiris’ sense of subjugation. Kashmiris have often told me that the decline of their mother tongue—Kashmiri—is a symbol of the decline of Kashmiri identity itself, which has been brought about by deliberate policies followed through the centuries by foreign invaders to decimate the mother tongue in favor of other languages, such as Sanskrit, Persian, Urdu, and English. Kashmiri, they lament, is now spoken only by those who have left Kashmir and are settled elsewhere in India or abroad, and routinely commend my ability to converse in (albeit accented) Kashmiri.

Their sense of loss regarding Kashmiri is compounded by the fact that the younger generation of well-to-do Kashmiris prefer to speak in Urdu and English rather than their own mother tongue. Some young people even go so far as to admit being unable to speak the language at all other than in broken sentences. Kashmiri, the older generation laments, has thus become the language of the poor. But much like in the rest of India, where Hindi is spoken (albeit with a liberal dose of English) more widely than might be expected given the pervasiveness of English, Kashmiri too (with a liberal sprinkling of Urdu and English) seems to be the default language for Kashmiris of all classes and ages even today, at least at home and on the street.

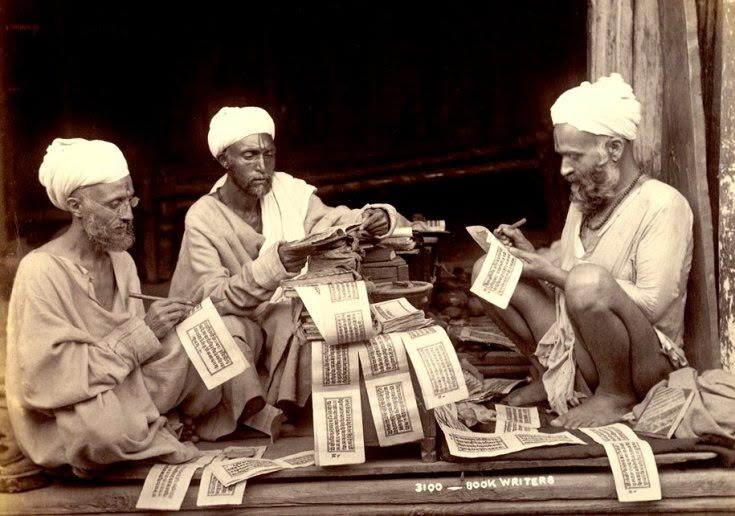

Kashmiri is, in many ways, a unique regional language. It has survived through at least two millennia mainly without a specific script and largely as an oral language. A script specifically suited to the vowel sounds of the language, called Sarada, which drew on the Sanskrit script, was developed in the first millennium, but had gone into decline by the sixteenth century with the more widespread use of the Persian script. Kashmiri dominated the oral sphere in the centuries that followed until the eighteenth century, when the more extensive adoption of the Persian script, including for Kashmiri, led to its reemergence as a textual language.

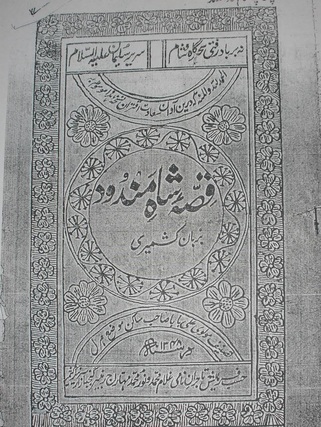

Kashmiri in Persian script

Kashmiri in Persian script

Just as until the middle of the second millennium, the relationship between Sanskrit and Kashmiri had been more than simply one of domination of the latter by the former, the relationship between Persian and Kashmiri too was a more complex one than is usually alleged in the domination/subjugation model. Persian took on the role of cosmopolitan vernacular while Kashmiri continued as the regional vernacular or the mother tongue; into my grandparents’ generation in Kashmir, both Hindus and Muslims, and even the largely unlettered, could read and write in Persian while speaking Kashmiri to each other. As the Mirwaiz Kashmir put it so well in the 1940s: “Our common dialect is Kashmiri and our common language Persian.”

This does not mean, however, that Kashmiri was accorded second-class status, because in Kashmir’s narrative sphere, Kashmiri and Persian interacted as equals, drawing on the store of tales, poetry, and histories from each other’s repertoires. Persian qisse (stories) were translated into Kashmiri poetry, and then recorded textually as well as performed by wandering minstrels and storytellers, even as Persian historical narratives recorded the Kashmiri stories that had been circulating in the Kashmiri narrative world for centuries, thus bridging the oral and textual spheres.

The historical memory of the land and its people that created a sense of belonging to Kashmir was a result of this synergistic relationship between Kashmiri and Persian (much as it had been a result of the earlier relationship between Sanskrit and Kashmiri, their synergy evident in the verses of Lal Ded and Nund Rishi).

This does not mean, however, that Kashmiri was accorded second-class status, because in Kashmir’s narrative sphere, Kashmiri and Persian interacted as equals, drawing on the store of tales, poetry, and histories from each other’s repertoires. Persian qisse (stories) were translated into Kashmiri poetry, and then recorded textually as well as performed by wandering minstrels and storytellers, even as Persian historical narratives recorded the Kashmiri stories that had been circulating in the Kashmiri narrative world for centuries, thus bridging the oral and textual spheres.

The historical memory of the land and its people that created a sense of belonging to Kashmir was a result of this synergistic relationship between Kashmiri and Persian (much as it had been a result of the earlier relationship between Sanskrit and Kashmiri, their synergy evident in the verses of Lal Ded and Nund Rishi).

Kashmiri adapted yet again when Persian was replaced by Urdu as the language of administration in the late nineteenth century and the language of the Kashmiri nationalist movement in the 1930s and 40s. Even though the movement itself did not take on a linguistic character, Kashmiri poetry was heavily influenced by Urdu literary trends, particularly the Progressive Writers’ movement. The Kashmiri verses of Ghulam Ahmed Mahjoor, Abdul Ahad Azad, Zinda Kaul, and Dina Nath Nadim, among others, celebrated the putative Kashmiri nation, its ties to the land, and its people. Drawing on nationalist and socialist themes of the Progressive Writers’ movement, this poetry took on the tyrannies of the Dogra state as well as the first National Conference regime of the early postcolonial period through its trenchant, albeit veiled, critiques of the government and its policies, reminding Kashmiris of the difference between what they had struggled for and what they had achieved in 1947.

Dina Nath Nadim’s poem, ‘I Will Not Sing Today’ (1950), (which both my parents can recite verbatim and which still moves them to tears) not only registered a strident protest against the invasion of Kashmir in 1947 and its reduction to a piece of disputed territory, but also introduced to Kashmiri poetry blank verse with a specific musical cadence especially suited to Kashmiri:

I will not sing today,

I will not sing

of roses and of bulbuls

of irises and hyacinths.

I will not sing

Those drunken and ravishing

Dulcet and sleepy-eyed songs

No more such songs for me!

I will not sing those songs today.

Dust clouds of war have robbed the iris of her hue,

The bulbul lies silenced by the thunderous roar of guns,

Chains are all a-jingle in the haunts of hyacinths.

A haze has blinded lightning’s eyes,

Hill and mountain lie crouched in fear,

And black death

Holds all cloud tops in its embrace.

I will not sing today

For the wily warmonger with loins girt

Lies in ambush for my land….

I will not sing

of roses and of bulbuls

of irises and hyacinths.

I will not sing

Those drunken and ravishing

Dulcet and sleepy-eyed songs

No more such songs for me!

I will not sing those songs today.

Dust clouds of war have robbed the iris of her hue,

The bulbul lies silenced by the thunderous roar of guns,

Chains are all a-jingle in the haunts of hyacinths.

A haze has blinded lightning’s eyes,

Hill and mountain lie crouched in fear,

And black death

Holds all cloud tops in its embrace.

I will not sing today

For the wily warmonger with loins girt

Lies in ambush for my land….

And today, despite the near-ubiquity of English, the most poignant expressions of loss, pain, and mourning by Kashmiris in the context of years of insurgency can be found in Kashmiri poetry. It is in this poetry that reside the deep feelings of nostalgia for the more peaceful, bygone times and the sheer dread of the precariousness of life in a society enveloped by violence. Kashmiri poetry by Brij Nath Betaab, Rukhsana Jabeen, Naseem Shafai, Maqbool Sajid, and many, many others, draws on the multiple, overlapping influences of Sanskrit, Persian, Urdu, and English to capture the physical, psychological, and spiritual wounds on Kashmir’s body politic and Kashmiris’ bodies. At the same time, contemporary Urdu and English writings by Kashmiris, which also articulate similar emotions, are imbued with the Kashmiri idiom and redolent of the landscape that has been and continues to be such an important feature of Kashmiri oral and textual narratives.

Since I grew up outside Kashmir, Kashmiri, in which I conversed with my grandparents, who narrated stories, sang songs, and recited poetry in the language, and which my parents to this day speak to each other and to my sister and I (no matter the language we choose to respond in), has been one of our most enduring connections to what might otherwise have felt like a rather distant land of their birth. Indeed, it might now be the only remaining connection to Kashmir for my parents as well (besides the Kashmiri food that we eat at home). This mother tongue or regional vernacular binds us to a Kashmiri identity no matter where we are in the world, and it will persist, as Kashmiri identity itself, through future generations, albeit in a different form and in diverse ways.

Chitralekha Zutshi, first posted in September 2016

do read the other episodes in Chitralekha Zutshi's Kashmir Journal