Kashmir Journal: Photographing Kashmir

In an occasional series for KashmirConnected, the eminent historian of Kashmir Chitralekha Zutshi writes about her experiences across the Valley and the manner in which the past moulds Kashmir's present

There is a small, sepia photograph in one of our family albums of my very young sister, sitting fearfully atop a horse in Pahalgam, with majestically scenic vistas and the gushing Liddar in the background. Since then, there have been many family and research visits to Kashmir, and hundreds of photographs of Kashmir’s peerless landscape and natural beauty that have collected in our albums, digital and otherwise. No matter how many times one visits the gardens at Nishat and Shalimar, or the endless meadows at Gulmarg, or the fierce rivers at Pahalgam, or the forests at Lolab, or indeed the snow-capped mountains that appear in different guises around the valley, one is reminded anew of their resplendence and compelled to photograph them.

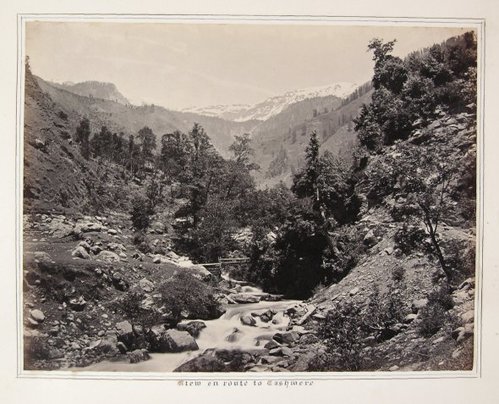

Kashmir is one of the most photographed places in the world, not so much for its architecture or its people, as for its landscape. In many ways, the art of landscape photography in late-nineteenth-century British India emerged and was honed aesthetically in the context of Kashmir and the innumerable natural panoramas it presented to the landscape photographer. Indeed, even in the international context, landscape photography in Kashmir reached its technical height at least a decade before it attained the same levels in other parts of the world.

Kashmir is one of the most photographed places in the world, not so much for its architecture or its people, as for its landscape. In many ways, the art of landscape photography in late-nineteenth-century British India emerged and was honed aesthetically in the context of Kashmir and the innumerable natural panoramas it presented to the landscape photographer. Indeed, even in the international context, landscape photography in Kashmir reached its technical height at least a decade before it attained the same levels in other parts of the world.

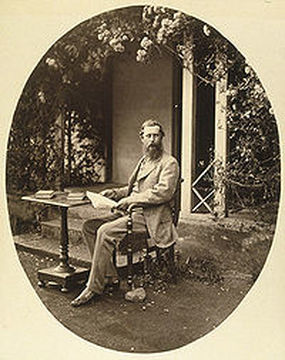

Samuel Bourne, the most well-known of British Indian photographers, who worked for a photo studio based in Shimla (and later Calcutta) as its travelling landscape photographer, spent nine months in 1864 trekking through Kashmir and living for a few weeks in Srinagar photographing its landscapes and cityscapes. His observations of the many landscapes he encountered during his travels in India were published in a series of essays in the British Journal of Photography. At his first glimpse of the Valley of Kashmir, he wrote, ‘What a scene was the whole to look upon! And what a puny thing I felt on that crest of snow!’ Throughout the essay, he complains about the inability of photography to capture the ‘superb mountain chains’ surrounding Kashmir, which ‘dwindled down to a low faint line on the horizon hardly noticeable’ in photographs.

William Baker and John Burke, who owned a photography studio based in Murree, spent the years between 1864 and 1868 photographing Kashmir’s many valleys, rivers, mountains, and meadows. Their photography trips were professional enterprises that involved large retinues that traversed rough, mountainous regions with heavy equipment and laid down elaborate campsites for days at a time, as the photographers navigated their vicinity waiting for the exact right combination of light and shade to taketheir photographs.

Photographic competitions held annually in British India encouraged the development of landscape photography and fueled contests among leading photography firms, British military officers, and amateurs. Most of the first- and second-place winners of these competitions between 1861 and 1875 were photographs of Kashmir’s landscape, usually either by Bourne or Burke. This not only made these photographs coveted in aesthetic terms—with their obvious links to the Victorian high-artistic tradition of landscape painting—but also in commercial terms, with Kashmir’s beautiful landscapes selling more than any other consumer photographic subject in the late nineteenth century. As framed or mounted photographs, postcards, and cards, images of Kashmir’s cool landscapes sold like hotcakes in the plains of British India, and in London and other European capitals, where Kashmir’s beauty had been rendered legendary by the many travelogues published by those trekking through the Himalayan region in the nineteenth century.

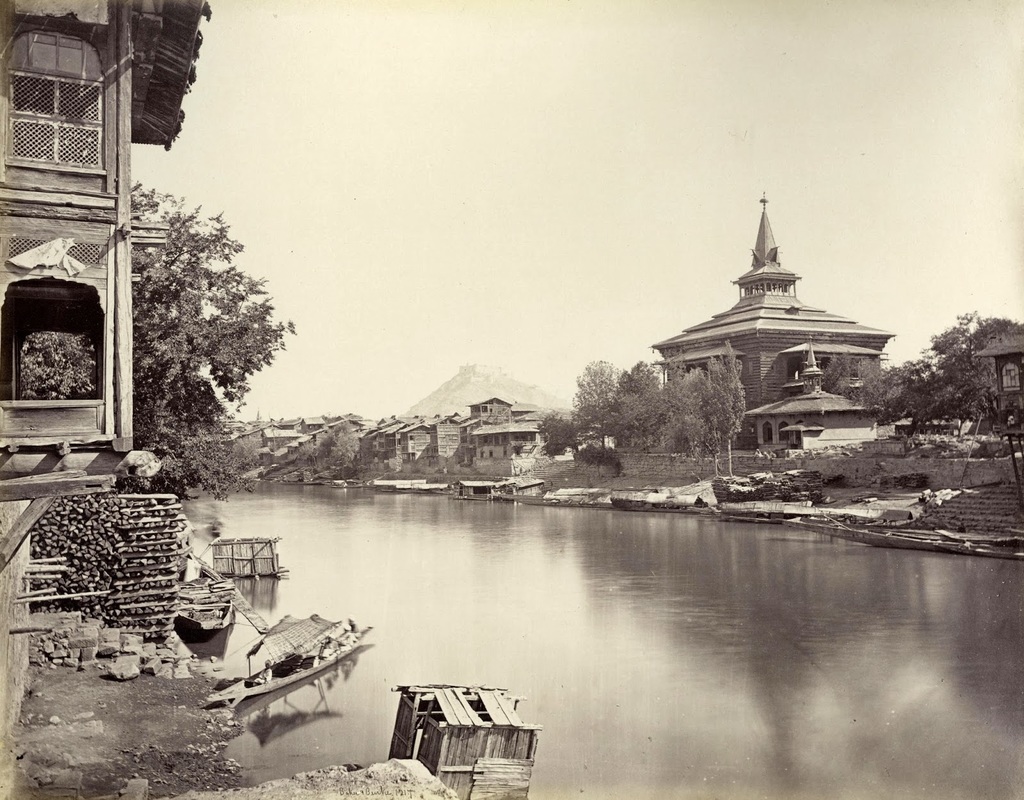

These photographs served to confirm Kashmir as a territory of desire—an orientalized space ensconced in the mountains away from the ravages of the industrialized world. Other than in the few portraits by Burke, Kashmir appeared in these photographs as a space devoid of humans and human activity, where the natural world ruled supreme. (Burke’s collection of Kashmir photographs is unique in the sense that he was perhaps the only photographer who was also interested in human subjects in Kashmir, and has left behind portraits of dancing girls, the maharaja of Kashmir, a Kashmiri woman, and a Kashmiri gentleman, amongst some others.) While discussed in some European narratives from this period, the natural disasters that wreaked havoc on Kashmir’s landscape, or the terrible hardships suffered by its people, did not make an appearance in these photographs. Kashmir’s image as the ‘Happy Valley,’ created by landscape photography, was then popularized further in European travel narratives to the region throughout the late nineteenth century.

Not surprisingly, thus, the history of photographing Kashmir is intimately tied to its emergence as a center of tourism. The Mughals, who adored Kashmir and immortalized its beauty in poetry and painting, were the first to promote Kashmir as a destination for Indian and Persian elites. However, the tourist industry in its modern form took shape in late-nineteenth-century Kashmir, as Europeans from the plains of India and from Europe began to flood the region during summers. So great was this traffic that the maharaja passed a law that Europeans could only live on houseboats, to prevent them from buying-up all the land in Kashmir.

It was in this context, as a thriving center of tourism by the early twentieth century, that Srinagar attracted the interest of a young self-taught photographer from Gurdaspur, Punjab, Amar Nath Mehta, who decided to move there along with his brother to set up a photography business. Named Mahatta & Co., their studio started on a houseboat in 1915 and expanded to a shop on the bund in Srinagar (which still exists and is run by the founder’s grandson, Jagdish Mehta) and another in Pahalgam. Mahatta did many different kinds of photographs of Kashmir, some that continued the tradition of photographing its bucolic and mountainous landscapes, but many that chronicle the transformation of these very landscapes into tourist destinations beyond compare, and later, into sites of conflict.

People are much more visible in these photographs than in the photographs by British Indian landscape photographers of the earlier period. The royal family makes an appearance numerous times with its European guests, and the fauna of Kashmir arrayed at their feet, a result of the hunting expeditions that were part of the elite tourist experience in early-twentieth-century Kashmir. Houseboats and shikaras on the Dal Lake, chock full of visitors, were popular subjects of these photographs, as were portraits of European visitors to Kashmir. These photographs were made more vivid by the introduction of hand-tinted color in the 1950s. Also in the same period, local studios such as Precos (strategically located near the Regal cinema hall) had emerged in Srinagar to cater to the demands of the Kashmiri population, especially the youth. There is a beautiful full-length photograph of my mother as a young woman taken at Precos in the early 1960s.

In the meantime, Mahatta’s photographs had vividly captured the increasingly turbulent politics of Kashmir in the 1940s. As the official chroniclers of the accession drama and the India-Pakistan war in 1947-48, the studio photographed M.K. Gandhi surrounded by Kashmiris during his visit to Srinagar in August 1947; Jawaharlal Nehru making his famous speech at Lal Chowk, Srinagar in October 1947, with Sheikh Abdullah by his side, vowing to stand by the people of Kashmir; colonial troops stationed in Srinagar in late 1947; Indian Air Force planes flying over the valley in October 1947; and the aftermath of the attack on the town of Baramulla in November 1947, among other scenes of discord.

These disquieting images, alongside the more serene ones of Kashmir’s landscapes, replay the constant tension between the twin representations of Kashmir as a zone of conflict and a paradise on earth, and the deeply unsettled politics simmering beneath the surface of its beautiful landscapes that not all photographs can capture. But perhaps more significantly, a different kind of photograph can remind us that Kashmir is more than simply a conflict zone or the most beautiful place on earth; for the people who live there, it is simply home, a place where they conduct their everyday life—studying, worshipping, shopping, eating, and celebrating the beauty of their homeland with family and friends.

Chitralekha Zutshi, first posted April 2016

do read the other episodes in Chitralekha Zutshi's Kashmir Journal