Kashmir Journal: Srinagar

Srinagar, the capital of the present state of Jammu and Kashmir in India, has maintained its status as the capital city of Kashmir at its current site since at least the sixth century, making it one of the oldest capital cities in the world. It was founded by King Pravarasena II as Pravarapura, and although some later rulers attempted to build alternate capitals, these cities were quickly abandoned in favor of Srinagar. Sanskrit texts from Kashmir, including Kalhana’s Rajatarangini, describe it as a city on a citadel located in the auspicious landscape of the Kashmir Valley.

Srinagar’s great natural advantages, including the river Jhelum, which meanders its way through the city and acts as the main artery of communication within, while also linking it to other parts of the Valley; its strategic location, naturally bounded as it is by mountains, which makes it invulnerable to attack; its rough equidistance from Jammu, Rawalpindi, Leh, and Gilgit, thus connecting it to the main trades routes leading to South and Central Asia; and its lakes, such as the Dal and Anchar, which provide its population with a bountiful supply of food, has cemented its position as the heart of the Kashmir Valley.

Successive dynasties that ruled Kashmir laid claim to the city and lovingly adorned it with canals, bridges, temples, shrines, gardens, marketplaces, industries, and much else. Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin, for instance, imported paper-makers and book-binders from Samarkand and settled them in the Nawa Shahr district of Srinagar, thus making the city a center for the production of durable paper, bookbinding, and fine calligraphy. As a whole, the Kashmir Sultanate (1339-1530s) patronized the building of numerous shrines in the city—usually in elegantly carved wood—in honor of the Sufi mystics who came to Kashmir throughout the period, and who in turn endowed the Sultanate with political legitimacy and ensured Kashmir’s transition to Islam. Several of the city’s seven bridges over the river Jhelum that link its two sides, including Zaina Kadal and Ali Kadal, were also constructed during the Sultanate.

By the time Kashmir came under the purview of the Mughals in the mid-fifteenth century, the city of Srinagar filled visitors with awe and delight. Mirza Haider Dughlat (Babur’s cousin and Mughal commander), who ruled Kashmir as Humayun’s representative from 1540-1550, wrote with wonder at Srinagar’s architecture in Tarikh-i-Rashidi: “In the town there are many lofty buildings constructed of fresh cut pine. Most of these are at least five stories high and each story contains apartments, halls, galleries and towers. The beauty of their exterior defies description, and all who behold them for the first time, bite the finger of astonishment with the teeth of admiration.”

The intricately carved wooden architecture described by Dughlat makes Srinagar a distinctive city in South Asia, but at the same time renders it vulnerable to fires, many of which have engulfed and destroyed parts of the city throughout its history. It is also its shrines that have rendered Srinagar into a powerful urban space, because exercising control over these religious spaces has been and continues to be essential to gaining and maintaining power in the Valley and over its people. The early twentieth-century Kashmiri nationalist movement emerged on the site of Srinagar’s shrines, where battles over defining Islam and demanding economic and political rights were played out, and it was through shrines and their managers that the movement grew and spread through the city’s many neighborhoods and eventually to other cities and the countryside. All major Kashmiri political movements before this moment, and since, have begun in or over Srinagar’s shrines.

Nishat Gardens

Nishat Gardens

With the incorporation of Kashmir into the Mughal Empire in the late sixteenth century, the Mughal rulers set about transforming Srinagar as was befitting the capital of the paradise on earth, and the summer capital of the Mughal Empire. One of the most significant architectural contributions of Emperor Jahangir, for instance, was the creation of Shalimar Bagh on the banks of the Dal Lake; this was later extended and enlarged by Emperor Shah Jahan, and another garden, called Nishat Bagh, also on the banks of the Dal, was financed by Asaf Khan, Shah Jahan’s father-in-law. These terraced gardens with the Zabarwan mountains as their backdrop, overlooking the iridescent Dal Lake, and shaded by massive Chinar trees, drew on the waterfalls from the mountains and the resultant natural springs to stunning effect.

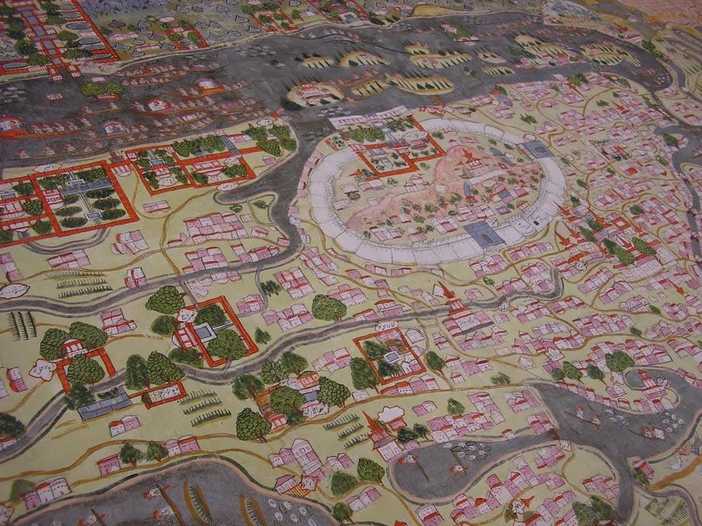

It was also during the Mughal period that Srinagar became the heart of the shawl trade that eventually drew Kashmir into trade networks that stretched via Ladakh from Tibet and Chinese Central Asia into Persia, the Ottoman Empire, Russia, Britain, and France. By the late eighteenth century, it was not uncommon to find Russian, French, British, Armenian, and Punjabi agents living in Srinagar to direct the production of fine shawls aimed at specific markets. While shawl weavers toiled away in squalor, shawl merchants lived in well-appointed mansions in the city. So closely were Srinagar and the shawl trade linked that the Dogra ruler of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, Ranbir Singh, commissioned the production of a finely woven shawl with the map of the city embroidered on it for presentation to the Prince of Wales on his visit to Kashmir. Thus Ranbir Singh asserted his right to rule Kashmir by claiming the city through its most important manufacture—the shawl.

Srinagar has always been a cosmopolitan place, attracting to itself people from all over the world for business and leisure, and by the late nineteenth century, it had become one of the most significant centers of the tourist trade in British India. Attracted by its salubrious climate and picturesque environs, Europeans and affluent Indians flocked to the city in the summer, occupying houseboats in and hotels overlooking its waterways. A photography industry emerged in its wake that attracted tourists as much as well-off locals, indelibly intertwining the lakes, bridges, and gardens of Srinagar with family histories and memories. The inhabitants of the city themselves could trace their ancestry to Persia, Central Asia, Tibet, and Punjab, amongst other places; they worshipped, studied, and worked the city, while enjoying its natural beauty around the year—even after the winter snows set in and the city had emptied of tourists.

Srinagar has always been a cosmopolitan place, attracting to itself people from all over the world for business and leisure, and by the late nineteenth century, it had become one of the most significant centers of the tourist trade in British India. Attracted by its salubrious climate and picturesque environs, Europeans and affluent Indians flocked to the city in the summer, occupying houseboats in and hotels overlooking its waterways. A photography industry emerged in its wake that attracted tourists as much as well-off locals, indelibly intertwining the lakes, bridges, and gardens of Srinagar with family histories and memories. The inhabitants of the city themselves could trace their ancestry to Persia, Central Asia, Tibet, and Punjab, amongst other places; they worshipped, studied, and worked the city, while enjoying its natural beauty around the year—even after the winter snows set in and the city had emptied of tourists.

Mining the countryside

Mining the countryside

Srinagar has undergone many travails through the centuries, flooding several times in the recent past, including in September 2014, and becoming transformed into essentially an Indian army barracks since the full-fledged insurgency against the Indian state began more than 25 years ago. Being engulfed in a state of perpetual, low-intensity warfare has taken a toll on the city’s gardens, architecture, canals, bridges, and its cultural character. Once flourishing movie theaters are now army camps, and people can no longer partake of the city’s many natural and architectural offerings as they once used to. Moreover, increasing population pressures due to rural-urban migration have led to urban sprawl,and this, accompanied by poor city planning, has created significant environmental degradation, shrinking its waterways and polluting the atmosphere. For instance, the mountains surrounding the city are being consistently denuded for construction projects, and the Dal Lake, once a shimmering body of water, has steadily dwindled into a pond, choked with garbage, sewage, and an explosive growth of algae.

In some ways, the capital of Kashmir faces similar trials facing cities across South Asia. Its challenges are greater, however, because of its geographical location, which makes it difficult for it to grow in size, and the political situation, which makes any headway in tackling urban planning near impossible. The city is often beset with curfews, strikes, and closures, with the government functioning only sporadically. High hopes were invested in the new coalition government that took power in 2015, especially in terms of introducing urban development programs and tackling environmental issues, but they foundered, like much else, on deteriorating political conditions, and Srinagar hasonce again been consumed by a prolonged period of unrest.

As the political center of the Kashmir Valley, Srinagar’s fortunes are tied to the Kashmir issue itself, and it could once again become a thriving capital city, the “Venice of the East” as it was once known, if the parties in the dispute could find a means of resolution.

In some ways, the capital of Kashmir faces similar trials facing cities across South Asia. Its challenges are greater, however, because of its geographical location, which makes it difficult for it to grow in size, and the political situation, which makes any headway in tackling urban planning near impossible. The city is often beset with curfews, strikes, and closures, with the government functioning only sporadically. High hopes were invested in the new coalition government that took power in 2015, especially in terms of introducing urban development programs and tackling environmental issues, but they foundered, like much else, on deteriorating political conditions, and Srinagar hasonce again been consumed by a prolonged period of unrest.

As the political center of the Kashmir Valley, Srinagar’s fortunes are tied to the Kashmir issue itself, and it could once again become a thriving capital city, the “Venice of the East” as it was once known, if the parties in the dispute could find a means of resolution.

Chitralekha Zutshi, first posted in December 2016

do read the other episodes in Chitralekha Zutshi's Kashmir Journal