https://www.epw.in/node/153204/pdf

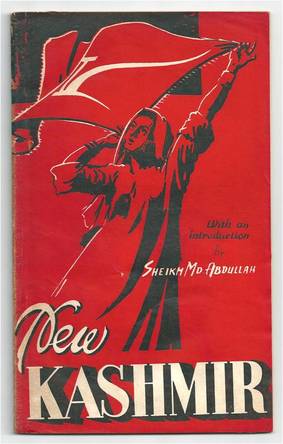

Kanjwal looks at the gender aspect of the National Conference's landmark 1944 'Naya Kashmir' ('New Kashmir') manifesto and further interrogates the advocacy of women's issues by looking at the autobiography of a prominent educationist, Shamla Mufti.

She argues in part:

Mufti’s autobiography is structured alongside three important moments in the history of modern Kashmir. The first, which encompasses the final two decades of the repressive monarchical rule of the Dogras in the state, describes her family background, childhood, and early marital and home life, and speaks to the multiple ways in which she, as a young Muslim female, was restricted both in relation to the Dogras as well as the prevailing conservative norms of the emerging urban, middle-class Kashmiri Muslim society at the time. Mufti was married at an early age, before she completed her schooling, and much of her narrative revolves around how she continued her education and gained employment, despite criticism from her family and her in-laws. The second moment, which arises in the immediate aftermath of partition and Kashmir’s disputed accession to India, as well as the rise of the Kashmiri-led National Conference (NC) government, narrates her experiences of obtaining higher education and working in a number of schools and colleges. It traces an “opening” that existed for a number of Kashmiri women, who were able to leave the confines of their homes under the new policies of the state government. Finally, the third moment, which is not covered as much in depth as the other two, provides a brief overview of increasing political instability in the state and its implications for everyday life, including the closures that it enforced on the period of “opening.”

While I will briefly address the first and the third moment, it is the second moment—the construction of the new NC state government and its policies for female empowerment—that will be the focus of this article. In doing so, it is argued that state sponsored feminism—while providing an upwardly socially mobile group of Kashmiri women opportunities for education, employment, and mobility—was paternalistic and ideologically motivated in its vision. As a result, no indigenous, independent women’s movement emerged in the state, and women’s issues became contested and linked to what was increasingly seen by them as an illegitimate rule.

It's an article which merits careful consideration and an important contribution towards a more gendered discussion of modern Kashmir.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed