Support for the move extended well beyond the ranks of India’s governing Hindu nationalist BJP – and what opposition there was focussed on the manner in which the changes were introduced more than the measures themselves. In the state itself, Hindu-majority Jammu and largely Buddhist Ladakh – both of which are content being part of India and resent the association with rebellious Kashmir – broadly endorsed the changes. But in the Kashmir Valley, overwhelmingly Muslim and the heartland of the Kashmiri language and culture, the move was greeted by a sullen fury and despair.

Ahead of the announcement, the Indian authorities imposed an extraordinary range of security measuresacross the Kashmir Valley to pre-empt protests and unrest: tens of thousands of additional troops were sent there; tourists and Hindu pilgrims were told to leave; schools and colleges were ordered to close; public gatherings were banned; freedom of movement was curtailed; the internet and both mobile and landline phone connections were switched off; and hundreds of people were arrested, including the leaders of constitutional political parties who have at times allied with the BJP. Kashmir was locked up and sealed off.

KASHMIR’S ACCESSION TO INDIA

The Kashmir crisis arose from a botched independence settlement when Britain pulled out of India in 1947. Jammu and Kashmir was a vast area stretching from plains north of Punjab deep into the Himalayas, and with no common thread beyond being part of the same princely state. It was up to princely rulers to decide whether to accede to independent India or to the explicitly Muslim nation of Pakistan. Three-quarters of Jammu and Kashmir’s citizens were Muslims; the ruling family were Hindus. The maharaja dithered but – his hand forced by an invasion of Pakistani tribal fighters – he eventually signed up with India and an airlift of Indian troops successfully defended the Kashmiri capital from the invaders.

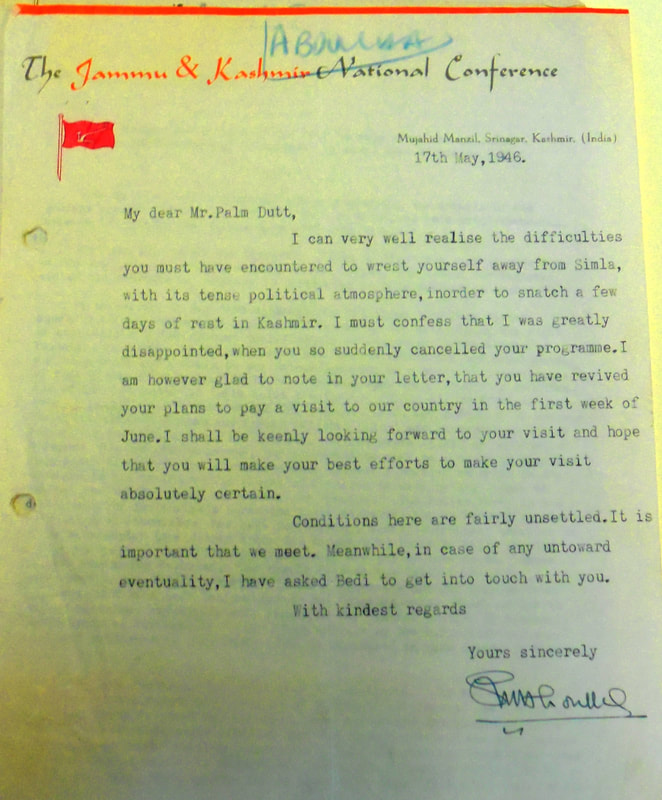

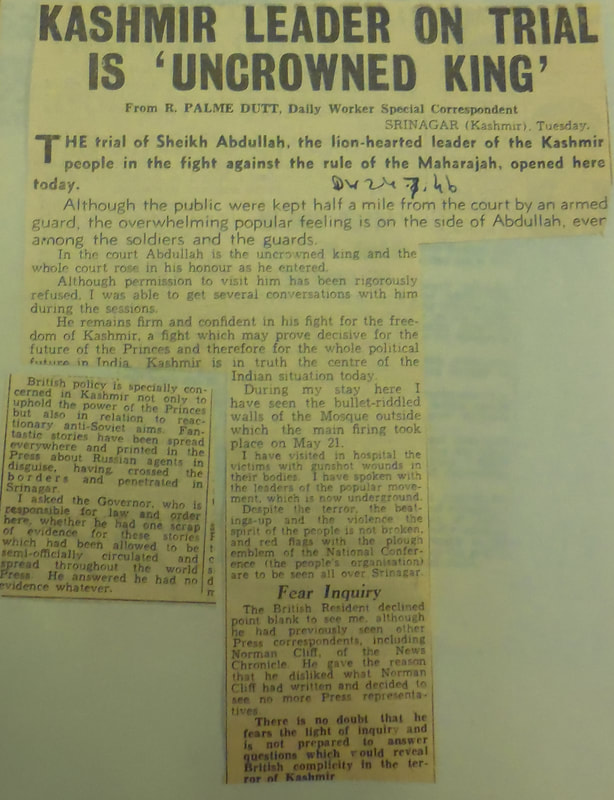

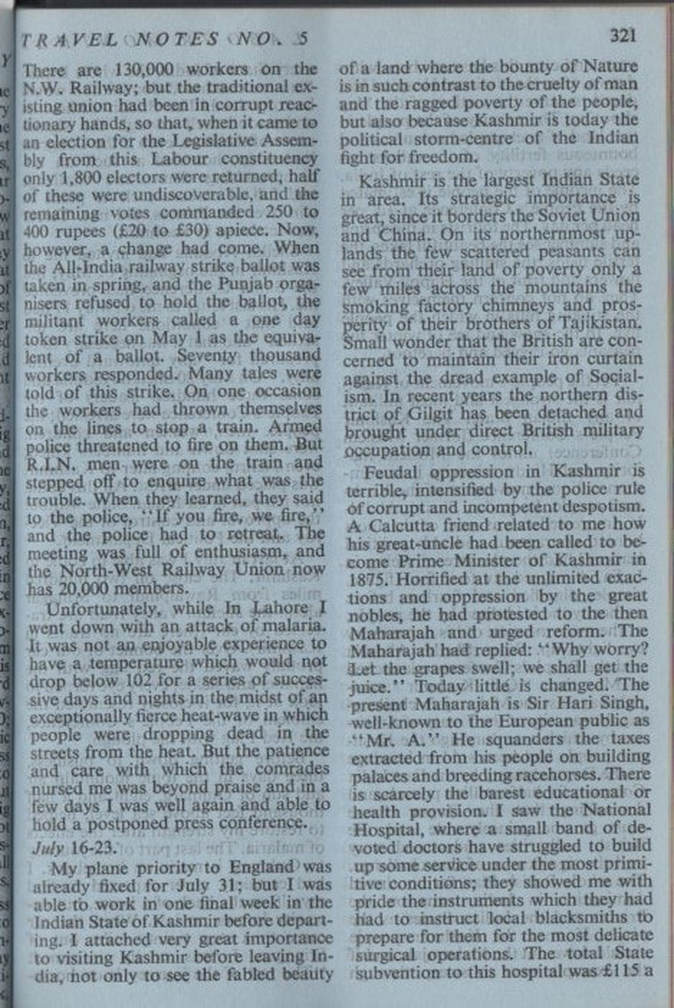

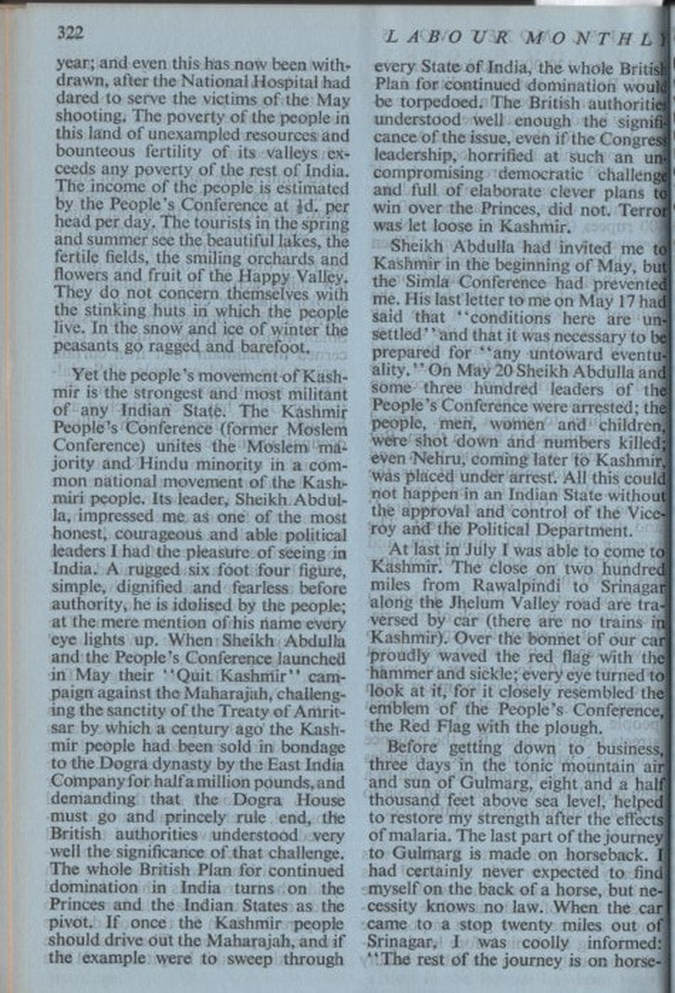

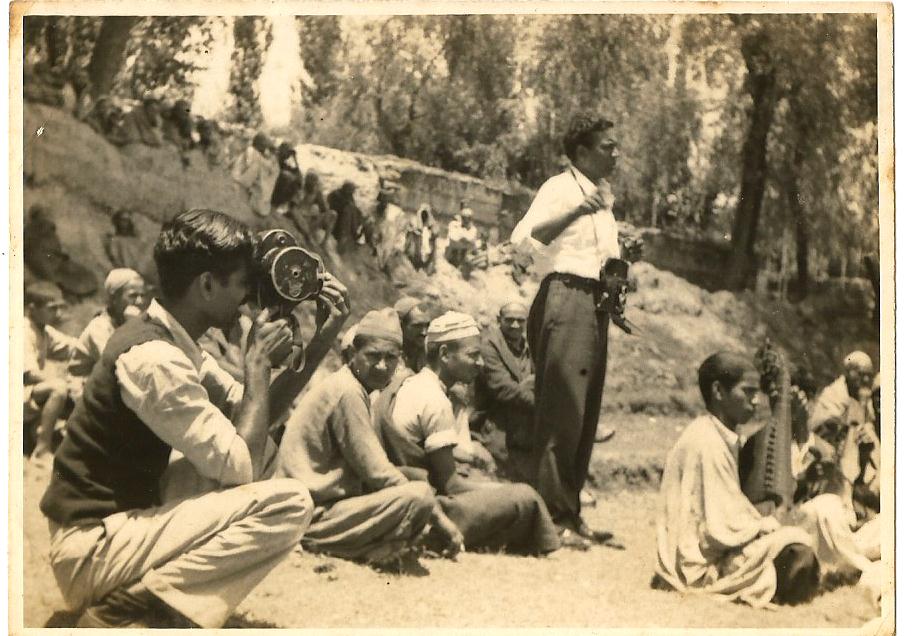

The decision to accede to India was also supported – at the time – by the maharaja’s most vociferous opponent, Sheikh Abdullah, a radical Kashmiri nationalist. The accession crisis was accompanied by a popular political mobilisation in Kashmir from which Sheikh Abdullah emerged as the key figure. At the same time, India and Pakistan went to war over Kashmir. That resulted in an informal partition of the state – though the larger part came under Indian control, including all the Kashmir Valley.India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, promised that Indian troops would withdraw from Kashmir once the invasion threat was banished and that there would then be a plebiscite about the region’s future. Neither promise was kept. But India did refer the Kashmir dispute to the United Nations – and to this day there are UN military observers in both sides of Kashmir, though to no practical purpose.

What became Article 370 of India’s constitution – giving Jammu and Kashmir special status and, on paper at least, considerable autonomy – was endorsed by India’s Constituent Assembly in October 1949 with little debate and no opposition. It was part of a political accommodation intended to make Kashmir comfortable within India – a goal which was never fully achieved. The unilateral tearing up of this special status is seen by many Kashmiris as the end of any aspiration in Delhi to rule Kashmir by consent. For Hindu nationalists, who resent a special status based in part on Kashmir’s Muslim identity, the goal has been to integrate Jammu and Kashmir fully into India – though it’s difficult to see how the revocation of Article 370 will in itself promote development or end terrorism, as the Indian government has claimed.

Sheikh Abdullah, after a few years in power in Srinagar, started talking up the prospect of an independent Kashmir – and that led in 1953 to his dismissal on Delhi’s orders and imprisonment. Ever since then, Delhi has repeatedly interfered in the governance of the state. The rigging of state elections in 1987 was a trigger for the separatist insurgency which erupted two years later – which was also armed, financed and encouraged by Pakistan.

In 2006, Pakistan’s military ruler, General Musharraf, came up with a four-point peace plan for Kashmir, which proposed that both India and Pakistan settle for control of the regions they currently hold and allow a measure of self-governance. The Indian government was keen to take this further – but Musharraf lost power before any substantial progress was made.

For Kashmiris, many of whom hanker for independence, Pakistan’s initiative raised concerns that again the future of their homeland was being decided without their active involvement. And that’s also why there’s such anger in the Kashmir Valley about the scrapping of Article 370. Once more Kashmiris have been denied any agency in how their region is governed. What we don’t yet know is how – once the curfew and other restrictions are eased – that anger will be expressed.

This article was first posted on History Workshop Online and is reposted here with their kind permission.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed