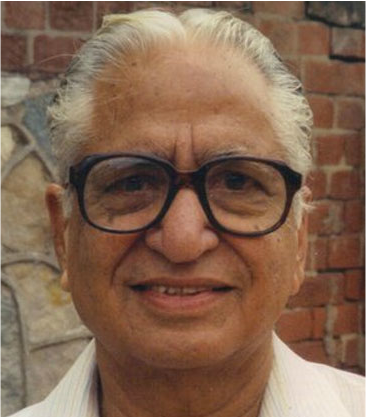

When I heard that Balraj Sahab had passed away this past August, I was overtaken by sadness, and also a pang of regret. I had plans to visit Jammu in November with the intention of spending some time with him, learning more about the entangled politics of the state of Jammu and Kashmir since 1947. In my experience, his was the most clear-headed and refreshingly honest voice on the subject. I had met him only once, in 2010, and although in frail health, he was lucid about the state of politics in Jammu and Kashmir. He told me that Kashmir’s politics was a prisoner of its past; it could not move forward until the intertwined interpretations about its history—both distant and recent—that define its political discourse in the present, could be disentangled. Truth was an incessant casualty in the process. With his death, I had lost my chance to learn more, but more importantly, we had lost someone who always told the truth regardless of how bitter it was, or how negative the consequences for himself.

"we had lost someone who always told the truth regardless of how bitter it was, or how negative the consequences for himself"

Fortunately, Balraj Sahab was a prodigious writer and has left behind a plethora of writings. He wrote on everything from Indian federalism to Communism in Kashmir to Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah, and much, much more. When I read his writings, I am struck by the simple yet potent logic he brought to bear on all his analyses. And these analyses were not merely academic for him; indeed he sought to put them into practice to solve the problems he saw plaguing the state. Two issues underlined Balraj Sahab’s politics over the years: re-centering the position of Jammu within the state of Jammu and Kashmir by allowing for regional autonomy, and the development of a healthy opposition within the state, which he saw as the basis of a democratic politics.

In pursuit of both causes, Balraj Sahab often clashed with the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference. An early member of the political party from Jammu, drawn to its progressive politics of land reform and economic equality, Balraj Sahab recognized that the party was overwhelmingly centered in the Kashmir Valley. If the party was to become truly representative, then Jammu and its people had to be given due representation within it, and by extension, a say and stake within the politics of the state. This could be achieved, in part, through a platform of regional autonomy, which allowed for all the constituent units of Jammu and Kashmir to function and develop equally well without encroaching on each other.

The second, related issue on which he spent his lifetime crusading was that, for democratic institutions to become functional and entrenched, the National Conference/Congress combine could not be the sole political voice within the state. J&K needed an opposition party or parties to challenge the dominant political players and to allow democracy to take root in the state. This was why he was a dedicated member of the Praja Socialist Party and refused to allow the party to be merged with the Congress.

Although he ran foul of the National Conference as a result of his politics (he was expelled from the party), Balraj Sahab spoke out vehemently against the Indian state for imprisoning its leader, Sheikh Abdullah, in 1953 and then intermittently until 1975. He incessantly mediated between Nehru and Abdullah and later between Abdullah and Indira Gandhi to bring about a rapprochement between the Kashmiri leader and the Indian center. He recognized that J&K was the true test of Indian democracy and secularism against which India’s democratic systems, its human rights record, and its record at preserving communal harmony would be measured. I daresay that he died a disappointed man in this respect, although not a pessimistic one, campaigning and writing for the truth until the very end.

I felt the huge void left by Balraj Sahab’s passing when I made my way to Srinagar and then Jammu in October and November. What was striking about him, I realized, was that he was universally respected. Political ideologues from across the political system admitted, rather wistfully, that he had always been right, that the political aspirations of the people of all the constituent parts of Jammu and Kashmir needed to be represented for the Kashmir tangle to be untangled. I wish he was still around, to help us make dispassionate sense of the recent election results in the state and what they foretell about its future.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed