“So how are you feeling about all this?”, asked a friend about the abrogation of Article 370 and the unprecedented security lockdown in Kashmir by the Indian government on August 5, 2019. I could not come up with a coherent answer. I had spent two days in an ATM queue in order to get enough cash to buy air tickets to fly out of Kashmir with my kids (debit and cards don’t work because of the network has been shut down) followed by half a day of waiting at the airport because of flight delays (no phones work so you can’t call the airport to check your flight status). And this was a relatively good day - the previous five days we weren’t allowed to move out of our house by armed Indian paramilitary men. I couldn’t get medicine for my four-year old who had a chest infection, supplies were running out and from day 3 on, we had no electricity. Most of my friends and neighbours - activists, trade union leaders and mainstream politicians - had been arrested and since the jails in Kashmir were all full, more than seventy had been sent to a prison in Agra, India. No contact with the outside world - it was basically a prison sentence without the pronouncement.

How does one describe such a catastrophic chain of events adequately and objectively, especially if one is caught up in it? All I could say at the time was that it was a Holocaust by other means - a State-led attempt at the erasure of an identity, a body of rights and citizenship; the attempted erasure of a community’s place in the world.

People who don’t know much about Kashmir wonder what warranted this sudden and unilateral revocation of a Constitutional provision that has allowed the people of Jammu and Kashmir to have their own Constitution, flag and the right to define its own citizenship with rights and privileges for nearly 70 years? The answer is the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (India's ruling party led by Narendra Modi) majoritarian agenda of homogenizing India after the pattern of an idealized Hindu past. Coming to power with a huge majority in the national elections in May 2019 has meant for the BJP the overt execution of its covert ‘Hindutva’ (anti-minority) agenda. The Indian Muslim who had hitherto been ‘othered’ and lynched with chilling regularity by Hindu extremists across the northern states, is now facing a State-led assault on her rights and citizenship. The abrogation of Article 370 in Kashmir and the National Register of Citizens that is externing hundreds of Assamese Muslims as ‘illegal immigrants’ are two sides of the same coin.

What rankled most was that the beaming Indian Prime Minister told the Kashmiris in a televised broadcast, that the mutilation of their state and identity was, ‘for them to progress at the same rate as the rest of India’. It was the White Man’s burden- repackaged as the Brown Man’s. Except it wasn’t.

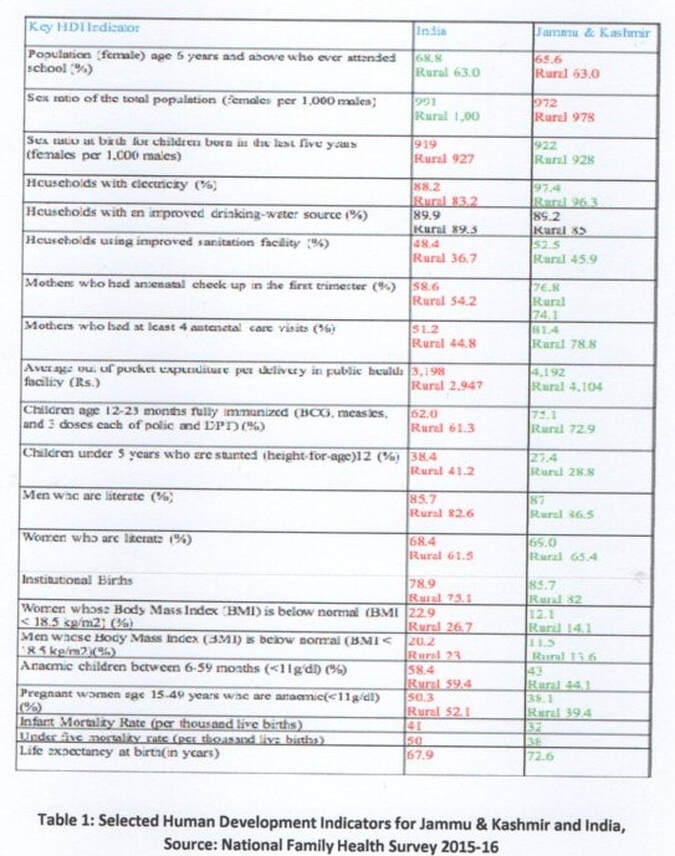

As figures from an Indian statistical survey show the erstwhile state is ahead of the national average in most Human Development Indicators:-

When comparing indicators across states the most striking fact is that Jammu and Kashmir has one of the lowest levels of poverty in India -10.3 per cent when the corresponding figure for India is 21.9 per cent [1]. It also has the highest percentage of people who have their own houses (96.7%) after Bihar (96.8%) [2]. Life expectancy at birth in Jammu and Kashmir (72.6 years) is again higher than the national average (68.8 years), even after the conflict that prevails.

This narrative of ‘accelerated development’ being pushed by the Indian government is not supported by facts at all. Instead it has been constructed to deflect international outrage over the government’s legal and security moves that have exacerbated a three decades old conflict and destabilised a region that is a potential nuclear flashpoint.

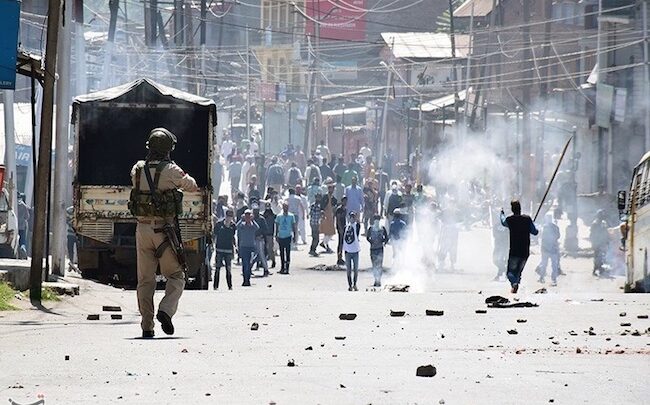

But this narrative is failing to find enough support outside India simply because of the enormity of the detentions and the draconian security measures the government has executed in the Kashmir valley. A population of 8 million people are restricted to their houses by 0.5 million troops, 4,000 political leaders (both mainstream and separatist) trade union leaders and activists are under arrest and all phone lines, mobiles and internet services for the entire region have been disabled.

The government has tried to defend these actions saying they are all in the interest of security but as Amartya Sen argues “That is the classic colonial excuse. That’s how the British ran …(this) country for 200 years.’’ The BBC, Al Jazeera and Reuters have been covering the blackout and the effect it has had on people’s lives, especially access to food and medicines. Even academic publication like the Lancet have written about the effect the restrictions have had on medical and emergency services, and the resultant effect on mental health.

With street protests continuing in the valley and Kargil, it is unlikely that the curbs on public liberty will be lifted anytime soon. But, until then, as Martin Luther King said “in the End, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends”.

[1] Press Note on Poverty Estimates in India based on the 68th Round of NSS (2011-12) data on

Household Consumer Expenditure Survey, March 19, 2012, Planning Commission, Government

of India, p.7

[2] Census of India 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed