Long ago intrigued by the mystery of Kashmir when my father entertained us with memories of his war years in India – tales of high snowy mountains, a close escape from a sinking houseboat, a tablecloth embroidered with delicate figures – I have visited Srinagar several times. In the spring when almond blossoms fill the air; in summer when houseboats huddle in the shade of green willows; and now in December, at the beginning of chillaikalan – the coldest, most severe 40 days of winter.

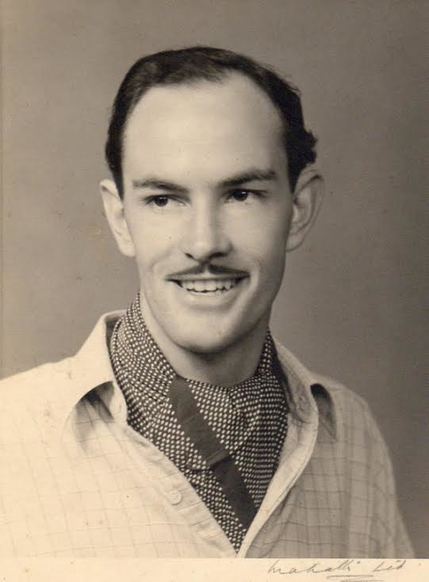

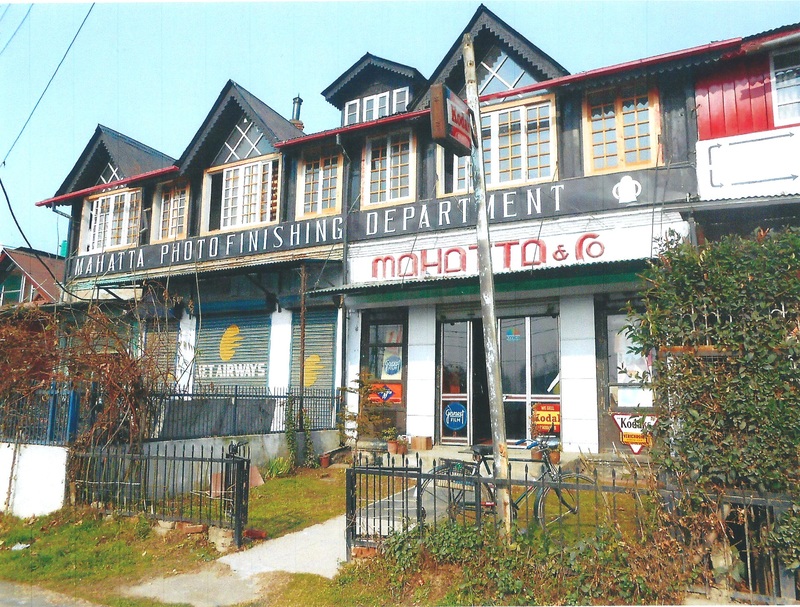

My father, Roy D. Williams, serving as a pilot with the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force), was based in India from 1942-45. In 2007 the discovery of his wartime diaries inspired me to trace his Indian footsteps, so a year ago, when a BBC article about Mahatta's Photo Studio in Srinagar caught my eye, it was with astonishment that I realised I have a portrait photo of Roy taken while on leave in Kashmir in August 1943. And quite clearly, at the bottom of the photo, is the Mahatta’s signature. I read that Mahatta’s, founded in 1915, continues as a glorious bubble from the past, run by Jagdish Mehta, a silver-haired gentleman clad elegantly in white. The shop still exists, but for how much longer? I had to go there. As soon as possible. Which meant winter.

Roy visited Kashmir twice. In the summer of 1943 and the spring of 1944. He travelled there by car from Murree (now in Pakistan), an eight hour trip over the mountains, before descending through a gorge for 100 miles, alongside rapids, fir, pine and poplar trees, arriving in Srinagar at 4.00 p.m. on 1st June 1943. On 2nd June, he wrote: glorious views of mountain range. Most lovely scenery ever seen on travels. Seduced by the beauty of Kashmir, he was a happy man.

Seventy-two years later, in December 2015, too terrified to face the mountain road from Jammu in winter, I arrived on a morning flight from Delhi, seated next to a rugged Kashmiri, brown and white beanie atop his suntanned head, a brown shawl edged with pink embroidery draped over his shoulders.

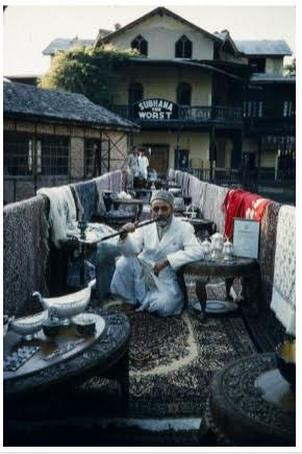

Mahatta's had inspired this visit, but was not my only mission – I also wanted to see Nedou's hotel where Roy went to dances, Nishat Gardens where he picnicked by moonlight, The Club, Gagribal Point where he went swimming, Dal Gate, and Third Bridge where he visited a mysterious Subhana mentioned several times in his diaries. In five freezing days I immersed myself in a Srinagar parallel to the usual tourist trail, stumbling into a world of extraordinary warmth and hospitality along the way.

When I first set forth for Mahatta’s, morning frost lay white on stone walls and blanketed the lake's wooden landing platforms. The lake was an icy, silvery sheen, boatmen in voluminous phirans huddled on richly coloured cushions in shikaras, kangri pots perched by their sides, while phiran clad men glided by on bicycles sagging under piles of coats, furry hats, and gloves. The world was cold, still, and surreal in its beauty.

Impossible to enter through barred gates and barbed wire, I took “creative” photos through holes in the old red wall, and was left wondering at the twists of fate which could leave such a fine old building, once witness to grand and happy times, in such a sad, uninhabitable state. Host to dignitaries including Lord Mountbatten and assorted maharajahs until its closure around 1988-89 when it became a military billet, alas much of its written records and history were lost in the floods of 2014 when the hotel was up to its neck in metres of water. The waterlogged gardens are perhaps a remnant of the Jhelum's waters, but if there are plans afoot to revive the hotel to its past elegance, there is certainly no sign of it.

| Entering its calm, dim interior of elegant wooden counters, glass-fronted wooden cabinets, old cameras, photos and photographic equipment is to enter another era. Alas, the owner Jagdish Mehta was not there, but his assistant, the tall and gracious Gul Mohammad rose from a chair by the door where he had been absorbed in a newspaper, and greeted me with quiet, smiling warmth. He told me that they no longer do portrait photos as the studio had closed, converted into a café, but he graciously took my photo with my own camera, and I took his, before descending to the downstairs café, once the studio, where huge black and white photos of old Srinagar street life cover the walls. I settled at a table, and like superimposed images, saw myself sipping tea in 2015, while the handsome 24 year-old Roy, cravat smartly tied, posed against the wall for his portrait in 1943. Oblivious to the future, and the fact that his daughter would one day be here too, hot on his trail. |

The wooden bridge is supported on pillars of interlaced wooden beams, works of art in their own right, and Moghul style kiosks provide shelter at intervals across the length of its elegant span. Two years ago I recall seeing the bridge in a shocking state of near collapse, so this renovation is a bright light indeed.

After seating me in front of the gas heater, and serving me warming cups of saffron tinted Kashmiri tea, Mr Gulzar proceeded to flourish the softest of Kashmiri scarves, a kashmir-mohair vest lined in silken pinks and blues, hunting jackets with leather elbow patches, plus-fours, knickerbockers, skirts, trousers and other extraordinary outfits from a time now past. He was a seductive salesman, (though I resisted his offer to make me a pair of plus-fours), and also a great source of information, telling me that as a child he accompanied his tailor grandfather to Nedou's, when cows were kept behind the hotel to ensure a supply of fresh milk.

| When I tell him that Roy made advance payment for embroidered work to a man called Subhana who then disappeared with the money, Gulzar's eyes lit up. Subhana “was a villain!”, he declared, known to have a bad reputation, so bad that one night somebody added the words “the Worst” to Subhana's shop sign. Speaking as though the villainish Subhana of 70 years ago was still there, he said that “the father was good, but the son went bad”. Indeed, but Roy, not to be outdone, returned the following year, contacted the Visitor's Bureau, tracked Subhana down at Third Bridge, and got his 50 Rupees back. During this story-telling, in a thoroughly modern moment, Gulzar's son Amjed went online and found a 1957 photo of Subhana seated on carpets and finery at Third bridge, a sign behind him announcing Subhana the Worst. |

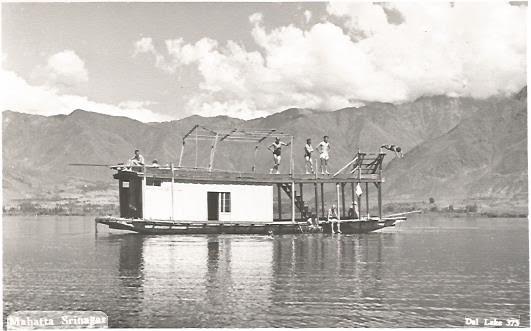

On arriving in Srinagar Roy joined the Club where he socialised, drank the occasional beer, and danced. His month long visits were active and idyllic - long horse rides before breakfast, walking and shopping on the Bund, buying film on the black market at 1st Bridge, and dancing at the Club, Nedou's and Nagin Lake. Returning from a late night dance one night he helped to open the lock gates at Dal Gate at 1.00 a.m. He went swimming at Gagribal Point, spending hours in the cool summer waters of Dal Lake. A “bathing boat” is still moored calmly off Gagribal Point near Nehru Park, proof that despite the now polluted waters, people still swim here.

Roy didn't confine himself to Srinagar. In May 1944 he travelled by mail bus to Pahalgam and set out on a three day trek to the Kolohai glacier, accompanied by Kashmiri guides, and enthralled by the magnificence of the mountains. But not all was idyllic – back in Srinagar, rain set in, and on Wednesday 17 May he wrote: Still raining steadily in morning. Continued throughout day till late afternoon. Took walk up to Bund. Spent evening on boat. Awakened at 2.30 A.M. by Alec. Annex capsized. Lucky to escape. All clothes and bedding saturated. River rose 3 feet due to heavy rains in mountains. I remember clearly his story of how the houseboat had broken its moorings, and trapped beneath a bridge, was flooding in the rapidly rising river.

More recently, in September 2014, Srinagar was metres under water when heavy rains swelled the Jhelum, burst open the lock gates, and flooded surrounding areas. Houses and hotels were submerged, people evacuated, hundreds died, and the damage can still be seen in collapsed buildings and a boardwalk by Dal Gate which rolls and sags as though in an earthquake.

And far from idyllic now is the bubbling undercurrent of discontent with the political situation. Young men talked of their desire for an independent Kashmir, of their frustration at the corruption and repression of free speech. Older men spoke with anger and tears in their eyes at the irresponsible destruction of lakes and waterways now turned to dry reed beds filled with rubbish.

When Roy left Kashmir, he made the return trip to Murree by bus, a tiring 12-hour journey over a road no longer accessible from Srinagar. Now travellers have the choice between a spectacular, hair-raising road to Jammu, or a short flight over snowy peaks. I chose to leave on a SpiceJet flight to Amritsar, sad to leave but relieved to escape the worst of chillaikallan when I feared a Kashmir sealed in ice and snow. Only five days there but an experience rich in the past and present intertwined, and the knowledge that the essence of Kashmir has not changed.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed