Let me start with a story of adventure, so nearly of misadventure.

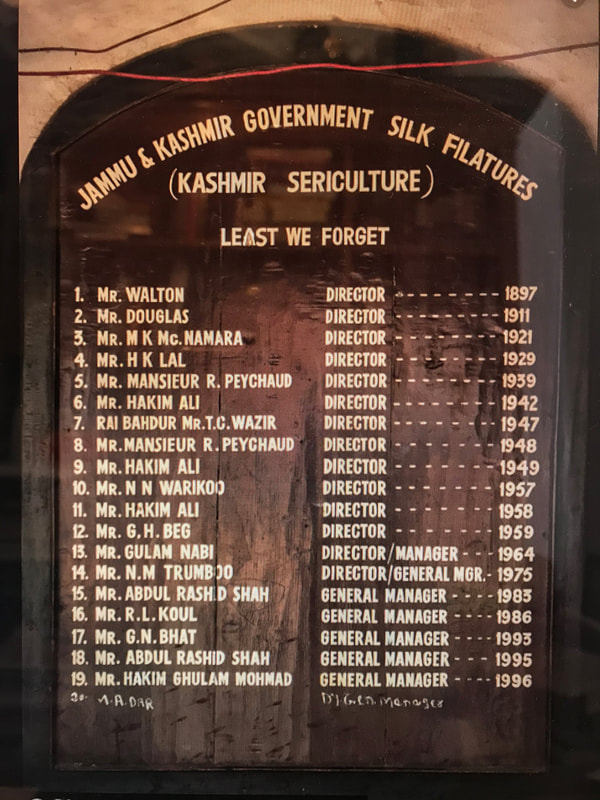

Late in the summer of 1921, my grandfather, Tara Chand Wazir (henceforth TCW), then a young man of 28 and working in the Sericulture Department in Jammu & Kashmir State, was on his way back from a tour of Europe where he had been sent on deputation to study different aspects of the silk industry. He took the steamship Paul Lecat from Marseille, and after a few days of rough sailing during which the passengers were confined to their cabins, they stopped at Djibouti for a few hours to refuel and deliver mail. The ship anchored a few miles from the shore because the sea near the coast was shallow. The passengers on board made up a motley lot - two Indians, including TCW, a Frenchman, a Greek, and a Swiss. Most of them had been pretty seasick on the journey and were eager to stand on solid ground for a short while. They took the opportunity provided by this stop and engaged a local boat to take them ashore. Two local men paddled the boat, front and back, and it was lit by a hurricane lamp as it had begun to get quite dark. A most intriguing incident followed, best told in the words of TCW [1]:

“When we were halfway between the ship and the shore, we suddenly saw a motorboat coming in exactly in transverse line - a few seconds and it would take our low African boat under it. Biscoeism in my blood asserted itself and used to boating as I had been in school days, I thought of saving the boat from the tragedy which was imminent. So, I stood up, tried to catch the external gunmetal bar running alongside the motor launch and with the manoeuvring of the feet put our boat in a position parallel to the launch so that the tragedy of drowning could be averted. The bar was polished and greased and I was heavy with my long boots, khaki drill suit with closed collar, Jodhpur-type breaches and evening cap. The watch I had purchased at Marseilles with mother of pearl casing was on my wrist. The momentum of the launch carried me off my boat after it had become parallel with the launch through the manoeuvring of the feet. I thus hung by the bar. The weight of my body and the clothes etc. could not long sustain me in that hanging position, when the grease on the bar did the trick and I fell down. I went vertically down into the sea, and while going down I felt all along that this was the end of my life, that now what would happen would be that the tragedy would be reported in papers. It would cause consternation in my family and all my hopes and aspirations would die with me. Above all, I thought about my old parents, my wife and my elder brother. By this time my feet touched the bottom of the sea and there was a rebound sort of thing and I came to the surface when I cried for help. I was trying to swim when something like a thick rope was thrown towards me by my fellow passengers... I caught hold of it and the friends in the boat picked me up. All that I remember is that I was put in a position where the sea water which I had taken in in plenty was drained out of my body, that my wet clothes were taken off, the Swiss gentleman gave me his own coat to put on and I fell unconscious.”

“Next day I woke up in my cabin in the ship, with the surgeon on board feeling my pulse and prescribing some medicine. My clothes were being dried on the deck. They then told me what had happened. When I stood up in the boat to save it, the French gentleman fancied that I was trying to save myself without caring for the safety of others in the boat, quite the reverse of my intention, and took out his revolver from his pant pocket to shoot me down. His neighbour the Swiss gentleman, understood my intention better, held the Frenchman’s hand and prevented him from shooting. In the meanwhile, I had fallen into the sea…The Greek gentleman had received some slight injuries on the nose, and the African boatman was missing presumably on the impact of launch on the front portion of the boat he had fallen into the sea and they told me that when the accident was reported to the boat commissioner, no trace of the African boatman had been found till then … Instead of going to the shore, the boat returned to the steamer, and I was placed in charge of the surgeon in the steamer, who left me to sleep for the night and saw me next morning when I woke to hear the story of this nasty incident. Afterwards when I met the French gentleman, I confirmed the Swiss friend’s interpretation of my movements and intention, and he had the fairness to apologize for the impulsive action he had proposed to take which might easily have proved fatal. This made the visit to Djibouti most memorable for me for it gave me a chance to say that not only had I seen the ‘fair fields and pastures new’ in Europe, but I had also had a glimpse of the bottom of the sea.”

What, then, is this ‘Biscoeism’ that TCW refers to? The reader may well wonder! To explain what he meant by it and what it might mean to scores of Kashmiri men, then and now, requires delving, howsoever briefly, into the history of modern education in Kashmir.

Kashmir’s fabled beauty had forever been spectacularly visible to travellers, adventurers and merchants – over time increasingly European – who came to escape the heat and dust of the plains, buy shawls, go hunting and trekking, write books, take photographs and paint exquisite scenes. Their sentiments about Kashmir would chime with the Mughal emperor Jahangir’s famous and oft-repeated exclamation, “if there is paradise on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here”. But for the ordinary inhabitants of the Valley, and some sensitive souls who came and stayed, this beauty gently receded into the backdrop, while the foreground that inexorably entered the eye and assaulted the mind was the poverty and wretched conditions in which the majority lived and survived.

The Dogra Rajah of Jammu, Gulab Singh, had supported the British in their battles, and subsequent victory, against the Sikhs who then ruled large parts of North India, including Kashmir. As a reward for this favour the colonial regime presented him with the Kashmir Valley in 1846 for the paltry sum of seventy-five lakh Rupees – a fact that still haunts the psyche of most Kashmiris – thus allowing the Rajah to create the State of Jammu & Kashmir as we know it now, and graduate in status from Rajah to Maharajah. The Dogra rulers showed little interest in investing in health, education, infrastructure, indeed in anything that would improve the welfare of their Kashmiri subjects; they concentrated on extracting maximum revenue from agriculture and handicrafts and peasants were drafted in to provide begar or forced labour for which they were not recompensed to carry heavy loads to remote areas like Gilgit and to build roads - to the point of leaving the populace in conditions of poverty and oftentimes near starvation. In this, unfortunately, they were no different from the previous Mughal, Afghan and Sikh regimes. Moorcroft describes the city as he saw it when he came to Kashmir in 1822 towards the end of Sikh rule:

“The general condition of the city of Srinagar is that of a confused mass of ill favoured buildings, forming a complicated labyrinth of narrow and dirty lanes, scarcely broad enough for a single cart to pass, badly paved, and having a small gutter in the centre full of filth, banked up on each side by a border of mire …. and the whole presents a striking picture of wretchedness and decay.” Quoted in Khan (1978) p. 16-17.

Sir Richard Temple, who visited Srinagar in July 1859, commented on the indifference of the Dogra Maharajah towards his Kashmiri subjects:

“I asked (the Maharaja) whether Srinagar city should not be drained and cleaned, and to this he answered, that the people did not appreciate conservancy, and that they would much prefer to be dirty than to be at the trouble of cleaning the place.” quoted in Khan 1978:18.

When Cecil Tyndale-Biscoe arrived in the city in 1891, nearly half a century later, to take over as the principal of the Christian Mission School (CMS), not much had changed, and he was shocked by the scene that confronted him:

“The day after my arrival, Knowles and I walked through the city … a walk not to be forgotten. I recall what attracted my attention most. The stench, the utter filth of the streets, notwithstanding the thousands of pariah dogs, starving donkeys and cows trying to get a living from this foulness. Most of the houses had thatched roofs. I was astonished to see not a single chimney, and only one house, that of the Governor, had glass windows.” (CT-B 1951, p.21).

This was the Kashmir that TCW was born into in 1893. The family had seen better days but were thoroughly impoverished at the time of his birth. His father had recently lost his job, and the great fire of 1892 had destroyed their house along with all its contents. As he recalled, “…when I began to see the light of day, my eyes met with the sight of nothing but remnants of debris in the compound or courtyard of our double-storeyed improvised house with no more than a plank roof to cover it which in inclement weather leaked terribly to our great discomfort.”

Opportunities for modern education were all but non-existent, at a time when the rest of British India was much ahead. Traditionally, Pandit boys were taught Sanskrit in pathshalas run by Brahmins, whereas Muslim boys were taught Arabic in maktabs that were linked to mosques. In addition, some Pandits taught Persian to both Hindu and Muslim boys in their homes, in return for a fee. With Persian becoming the court language, this, and some arithmetic, were added to the teaching. By 1872, the state had responded to repeated requests from the community and opened a few schools in Srinagar, but these mirrored the pathshalas and the maktabs.

This situation changed dramatically with the arrival of the Christian Mission Society in 1864, in the first instance to set up the first hospital in the city, followed by a school in 1880, both in the face of enormous opposition from the Dogra state. The first Christian Mission School was set up in the premises of the hospital, which had its own building by then, and started with about five students, but within a few years they were allowed to rent their own space and later to construct their own school. The principal of the school for the first ten years was Reverend J.H. Knowles, but it was only with the arrival of Reverend C.E. Tyndale-Biscoe in 1891 that the school took on its distinctive character.

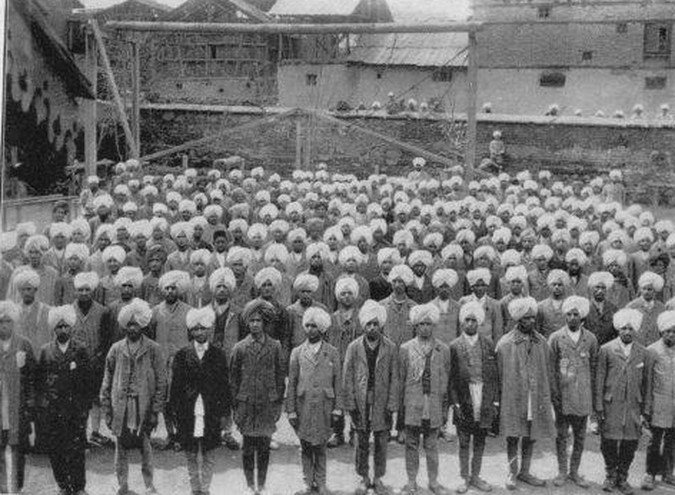

Biscoe was appalled by what he saw when he entered the school for the first time. [3] The boys, nearly all 250 of them Pandits at that time, came to school dressed in their pherans – the long, loose garment worn by Kashmiris, many of them holding a kangri (fire pot) under it. They ranged in age, with many of them 20 years or older; and most of them were married and were already fathers. Discipline was lax, there was no uniform, school was supposed to start at 11 a.m. but the students would saunter in till midday; absenteeism was rife, and all manner of religious functions were seen as a ready excuse for skipping school. The boys refused to take part in sports - being Brahmins they would not touch a person of another caste or religion, nor touch a football or an oar for fear of being contaminated by leather, they abhorred any form of physical exercise as it would make them muscular and make them look like lower caste men. Biscoe found the Kashmiris sickly, cowardly, dirty, superstitious, arrogant and lacking in moral fibre; they had no qualms about lying, cheating at examinations, or accepting bribes. The only redeeming feature of the Kashmiris, as he saw it, was their great sense of humour, and their acting skills.

A school-going father from the early days, from E.D. Tyndale-Biscoe (1930), page 3 - by kind permission of Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe.

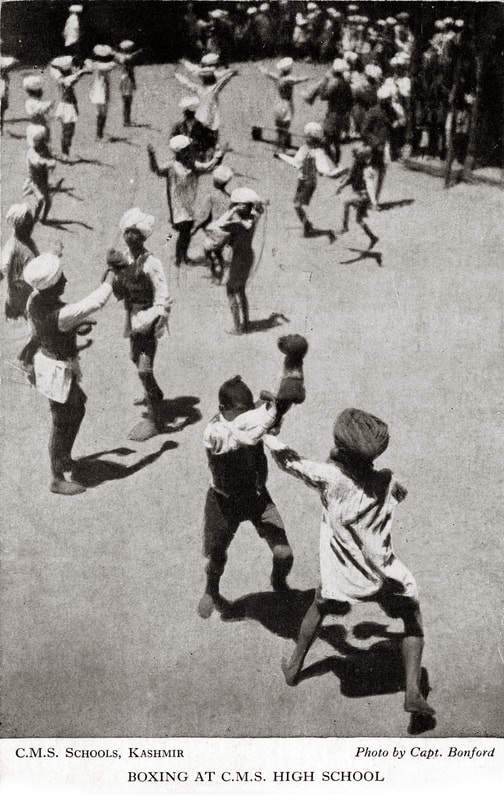

A school-going father from the early days, from E.D. Tyndale-Biscoe (1930), page 3 - by kind permission of Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe. Biscoe, never a particularly good student himself, was wary of the narrow limits of such learning as was available in books alone. What the boys needed, according to him, was a change of hearts and that could only be achieved through action and inculcating a spirit of service by practical example. For him education was only one part of the school curriculum, equally important were the development of physical strength and social service towards weaker members of society. Sports, including boxing, football, cricket, swimming and rowing were made a regular part of school activities, with inter-school competitions between the six CMS schools that opened in quick succession, and later with other schools, all of which also introduced sports as part of their regular activities. The annual regatta organised by the Biscoe school became an institution, and huge crowds started turning out on the riverbanks to watch the rowing and swimming events. For Biscoe, sporting activities were an important means for instilling fair play and team spirit in the boys. In addition, it built their physical strength and they learnt important skills such as rowing and self-defence which could be used for social service to help weaker members of society.

Biscoe did not shy away from tackling deeply entrenched social practices that would normally be considered outside the remit of a school. Boys who got married before the age of eighteen were charged double tuition fees, in an attempt to put an end to this custom. The school even took up thorny issues such as paedophile rings preying on schoolboys, pornography being peddled in the school and the city, and widow remarriage, going to the extent of organising marriages for widows and finding priests who would officiate at them. In fact the first remarriage of two young widows took place in May 1928 through the efforts of the school – the Brahmin priests who had agreed to perform the ceremony dropped out at the last minute, but the headmaster of the school, himself a Brahmin priest, stepped in and married them. This event was followed by relentless campaigning with the Maharajah to end this practice till he finally enacted a State Law permitting widows to remarry in 1933.

Biscoe’s approach was innovative, pathbreaking and dramatic for the Srinagar of those times; he stamped his distinct identity on the Christian Mission School to the extent that it began to be referred to, and still is, as the ‘Biscoe’ school. Initially he faced a lot of opposition, from the Dogra state, from the parents, and also from the boys. The Pandits, of course, saw their caste status being defiled, and the Brahmin priests threatened excommunication for the ‘unholy work’ that the boys were undertaking. Both Hindu and Muslim parents were united in their dissatisfaction with the emphasis given to sports and social service. After all, they were sending their boys to school to get a certificate that would give them access to jobs in the government bureaucracy, and any distraction was a waste of their children’s precious time. Protests were organised, petitions were sent to the Maharajah, letters were written to the press complaining about the school and about the methods employed by Biscoe, and even anonymous letters were sent to the Resident threatening to kill Biscoe if he was not immediately expelled from the State. A petition, dated 1 April 1908, from the Hindus and Muslims of the city to “Members of the Mission Society” ends with the following, somewhat amusing, complaint: “Therefore, please, Sir, transfer Mr. Biscoe, for he is exceedingly a bad man, illiterate, deceitful, ill-mannered, uncultured, cunning, and man too much fond of cricket.” (C.E. Tyndale-Biscoe 1920:33).

Opposition came from within the British and missionary community as well. In fact Biscoe was very nearly recalled from Srinagar on more than one occasion because “instead of preaching in the bazaar, I was filling my days out of school hours with all sorts of ‘goings-on’, calling out my boys in the night as well as in the day, to fight fires and above all teaching the school staff and boys to use their fists…” (C.E. Tyndale-Biscoe 1951:67). But he was always saved by a friend or a well-wisher who had visited the school and seen its impact on the students. In time, protests and opposition from all quarters came to an end; the school came to be recognised as a space free of caste and religious distinctions. Muslim boys started enrolling. The school’s activities were wholeheartedly supported and accepted, and henceforth sports, though not social service, became part of the mainstream curriculum followed by the few high schools and the undergraduate college that were subsequently set up by the Dogra state in response to the work of the missionaries and to the clamour among the population for more educational facilities.

Growing up, I had of course heard about the school from my grandfather who would often talk about his student days, and he was prone to exclaim “I am a Biscoe boy” from time to time, as and when the situation demanded. I didn’t know much else about the school, apart from the fact that it still existed and had the reputation of being a ‘good’ boy’s school. By then, several other schools, including another missionary school for boys and a convent school for girls had opened in Srinagar, providing competition to the Biscoe school. It was only when I arrived in Cambridge in the 1970’s and chanced upon a book by Biscoe while browsing in an antiquarian shop that I began to understand the wider significance and influence of the school. Over the years I was able to add to this collection of old books and photographs about the school, and Kashmir in general.

Biscoe appears to have been a man of contradictions. He was, of course, a missionary whose primary purpose in being in Kashmir was to convert the locals to the ways of Jesus. He believed fervently in this mission; in fact, he went to the extent of prophesying “…that Kashmir will one day be won for Christ” (T-B 1920:2). But he had a somewhat broader definition of Christianity. In his way of thinking it meant being a man who combined in himself the qualities of hard work, strength, kindness and service. He was a man of his times, a firm believer in Empire and the superiority of Western civilization, to the extent that he was a member of the India Defence League (Studdert-Kennedy 2004:857-858) but when asked by his European contemporaries if it was wise to train Kashmiri youth, lest they use their power against them, he would say: “My experience of life is that brave men respect brave men, to whatever country they may belong. It is of cowards that we must beware…If these Kashmir boys become true men, strong as well as kind, what have we to fear, if we too are men? We will grasp their hands as brothers.” (T-B 1920:21).

At the same time, he had an abhorrence, developed at a young age, for the slave trade in Africa. In his autobiography, he writes:

“When I was about six mother took my brother Ted and me to see our grandmother Tyndale at Oxford. On the table was a missionary box with a nigger boy on the top, standing with a broad-brimmed hat at his feet with a slit in it. Mother said that if we dropped a coin into the hat, the nigger boy would nod his head. So we dropped in a penny, and the little boy did as mother said. On our drive home we asked our mother about this little boy and she told us of the African slave trade. When Ted and I were in bed together that night, we promised each other that when we grew up we would go to Africa and set the niggers free. Ted did eventually join the navy, and when a midshipman, found himself off Zanzibar with the East Indian Fleet catching the slave dhows and setting the “niggers” free” (T-B 1951, p.21).

The desire to fight the slave trade never left him and as a young student in Cambridge he would arrange meetings in his rooms to attract more crusaders to this cause. He offered his services to work in Africa when he joined the Christian Mission Society, but that was not to be. Because of his poor health he was sent to Kashmir instead, where he continued to preach against what he saw as the most evil of practices, but this time to the boys in the school. TCW was one of the young boys on whom these teachings made an impression.

TCW’s own educational journey closely mirrors the unfolding of modern education in Kashmir. He commenced schooling, as did scores of other Pandit boys, in a pathshala run by a devout Brahmin. This must have been around 1897, I don’t know the exact date but have calculated it backwards from the date of his Matriculation in 1909. He spent only a short time in the pathshala and all he could remember of his days there was the absence of books, paper, ink, pens and other items of stationery. They were taught writing on a takhti (wooden tablet) on which letters were written with fingers or with thin reeds. Instruction was given in Sanskrit, of which he professed to remember not a single word. Within a very short period, a branch of the Biscoe school catering to primary school age boys opened near his house and he moved there. This happened by pure chance, on the recommendation of Asad Mir, whose family owned the building in which the school was accommodated, and who happened to be a friend of TCW’s older brother.

TCW joined the Biscoe school in the lowest class, a sort of kindergarten, and in his passage from one class to the next, he came across some “stalwarts among the teachers of the school”, but the most impressive of them all, according to him, was the Principal Tyndale-Biscoe. TCW writes that he was mischievous throughout his school days:

“Once I had failed to learn a lesson or perform a home task in Persian and the teacher Hari Kak prescribed the most cruel punishment, cruel by any standard as prevailing then or now, namely, a lashing with Suya (stinging nettle) all over the body. In fact I was made to lie for some minutes in an encasing of Suya plant till the whole of my skin was red with pimples and then in that month of mid-winter I was taken to the river nearby where I was given few dips in freezing water to mollify the pimples. Whether the pimples were mollified or not I cannot tell, but I am sure that I escaped death by a narrow margin and this through nothing short of a miracle. My people at home when they heard of this cruelty were greatly upset. They thought of protesting to the principal; they even thought of withdrawing me from the school. But neither the one nor the other proposal matured … I am sure if Biscoe had been apprised of the fact, he would have given the sack to the Persian teacher which he richly deserved.” [4]

How different these brutal methods of disciplining children were from the one’s Biscoe used!

“Biscoe himself once caught me in his Bible class when I reached the highest rung of the ladder in the school, i.e. fifth primary. A strict disciplinarian that he was, though equally regardful and affectionate towards his pupils, he found me laughing while he was haranguing us on some serious subject. But then he was Biscoe and nothing if not original in everything. The punishment he prescribed was of a novel kind, at least it struck me as such at that time. He brought a sheet of paper and wrote the words ‘LAUGHING MONKEY’ on it and tied it on the back of my coat and had me taken round all the classes. This punishment was more telling than a dozen lashing of a suya plant and dips in freezing waters of Jhelum could possibly be. But even this failed to deter me for shortly after I was promoted to first middle class and was shifted to the central high school at Fateh Kadal. I repeated the offence in Biscoe’s class and he was justifiably upset about the repetition of the offence and this time had me taken up with the same board of ‘laughing monkey’ on my back to the topmost ladder in the gymnastic compound and was left there in the full gaze of the school students who pointed the finger of scorn towards me. Now, at this distance of time, I find it difficult to explain why I got those laughing fits in season and out of season which earned for me the punishment I richly deserved … One thing however is certain that this was the end of the delinquency on my part.”

There were several aspects of the education that TCW received in Biscoe School that left an everlasting mark on him, and none of them had anything to do with the academic side of learning.

“One of the most unforgettable experiences I had in my high school days related to the annual day functions of the school and the way they were celebrated under personal instructions of Tyndale-Biscoe. The programme he chalked out for such occasions, all emanating from his fertile brain, unmistakably stamped him out as an educationist in the real sense of the term. True to the motto of this school ‘In All Things Be Men’, he first of all wished the students to be physically strong. For this he arranged … PT games of all kinds such as, horizontal and parallel bars, ladders and jhulas (swings), high and long jumps, drills with bars and clubs. This is to say nothing of aquatic sports, jumps in different positions from the roof of the school building into the river, swimming and boating competitions, which formed a source of attraction for most of the people in the city who came out and watched the scene, so unusual and unlike what they were accustomed to seeing. Other schools followed the lead of Biscoe School later on.”

“To avoid this penalty we had to learn swimming and pass a test held under the auspices of the school…From Gagribal point to the end of a nullah towards Rainawari we had to swim independently, if the enterprise were successful we were given a certificate, production of which would exempt us from the payment of the double fee. I had learnt swimming indifferently, so when I came in for the test, I collapsed halfway, but then the rescue arrangements consisting of boats and expert swimmers accompanying the examinees on trial were ideal and the experts at once picked me up. I had to wait for a year to renew the test and on the second attempt I was successful. I do not know if one of the main reasons for my good health did not lie in the physical training which I received in Biscoe’s school.”

One school event that TCW often talked about with great excitement was Biscoe’s brilliant idea of giving visiting dignitaries a ‘human’ welcome, as he used to call it. I didn’t quite believe this, maybe because I couldn’t visualise how it was done, until I chanced across a photograph of one such welcome in a book by Biscoe (1951:153). My excitement at finding photographic ‘evidence’ of what I had always thought of as a fanciful story was tempered by the fact that my grandfather had passed away a few years before and I could not share my find with him, nor could I ask him if he had been part of the welcome. I know now that he couldn't have been, as this 'living welcome' was staged only twice, both times after TCW had left school. Biscoe (1951) gives an account of organizing the first such welcome for the visit of the Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, and his wife to Kashmir in 1912:

“P.W.D. officers very kindly lent me a wire hawser…We anchored one end in the school compound and brought it over the roof of the school building, then across the river and fixed it to a tall tree on the opposite bank. On this hawser we hung the letters WELCOME, made of bamboos on which sixteen boys were to take their place, the boys being dressed in the colours of the Union Jack. This ‘living welcome’ was to hang thirty feet above the water …. Lord Hardinge told me afterwards that when he first saw the ‘welcome’ he thought that the letters were made of bunting, but just before the state barge reached it, I blew a whistle and immediately the ‘letters’ plunged into the river and swam ashore. Lord Hardinge doffed his cocked hat and cheered the boys.” (T-B 1951, p 151).

“The annual day function was almost invariably presided over by the Resident in Kashmir or some high dignitaries from British India, whose honoured wife, if present, gave away the prizes, medals, trophies and other decorations to winning individuals and teams. Academic distinctions i.e. proficiency in studies, though they had their rightful place in such awards, what was noteworthy was the large number of the prizes awarded for proficiency in games, ground as well as aquatic, and for social service such as cleanliness, saving lives in fire and drowning etc., helping the weak and the indigent and so on.”

"The Annual Day was held generally in the central school, but sometimes also outside. One of the most noteworthy of such functions outside was the one held in my school days at Gagribal point in Dal lake, where a most interesting demonstration was given of the slave trade which flourished in those days in African colonies and did not fail to contaminate the source of Colonialism and to bring about a revulsion of feelings against it in the public’s mind. Biscoe’s show was a most telling condemnation of the social evil as it prevailed in those days. I am not sure if Biscoe’s voice against the evil as demonstrated in the show was not as strong as that of any other individual here in this tiny state or elsewhere in the world. For myself it was a lesson which I could not forget in life, i.e., the bane of degrading life by enslaving it.”

An amusing and telling vignette that TCW paints is about the importance of passing examinations, illustrating Biscoe’s own sentiments when he says, “Before I came to this country I thought examinations most uninteresting, but here I find them full of interest and humour” (T-B, 1920:32). He was, of course, referring to the wide-scale cheating that was endemic, but also to the huge amount of fuss around the event. TCW recalls:

“The last recollection of school days relates to our Matriculation examination 1909. There was only one examination centre and that was the Sri Pratap College hall ... One should have seen the furore that there was in the college compound when the examinees came out for the intervals between the two meetings, morning and afternoon. Friends, relatives, Susralwalas, and all had come with sweets, baked mutton, cooked koftas, rogni roti and all that to regale their heroes with, for they were regarded in those days nothing short of heroes, little Caesers and Napoleons, though the countries they conquered were only some little books of indifferent merit which were prescribed as the course for the Matriculation by Punjab University to which the educational institutions in the state were affiliated. One should have also witnessed the tension which existed in our minds when the result was about to be announced. We were asked to collect it at the vice principal Mr Lucey’s residence in Sheikh Bag, made to stand in a row and then the result was announced one by one. When the time came for my name, so tense was the excitement that I thought that my heart would cease beating. Once the magic word “pass” came out of Lucey’s mouth, I jumped with joy and ran to announce this heart-elevating news to my kith and kin who were gathered in large numbers outside the premises. Jubilations and felicitations continued at home for several days which almost made us feel that we were made of some other clay than which goes in the composition of common mortals.”

TCW didn’t distinguish himself in school – he was an average student and an average athlete.

“For myself, I never had a distinction of ever winning a prize or distinction in school days. The nearest I came to it was when I succeeded in getting the much prized remark “Fair” on my English composition from Mr. Lucey, the vice principal who, himself a great scholar, somewhat of a taciturn temperament was very chary of giving any high complimentary remarks such as, “Good” or “Very good”, to say nothing of “Excellent” to any student on his home or class work, at least in my class.”

Academic achievement and plaudits came later when he stood first in J & K State in B.A History honours, and passed the M.A. History examination with a Distinction, earning him a place in the Roll of Honour in Government College, Lahore.

But Biscoe must have recognised some talents and qualities in TCW because he became a well-wisher, friend and mentor for life and helped him later on in all manner of ways, such as in assisting him to secure an exemption from the payment of tuition fees once he passed out of school and joined the local college. “The exemption was secured by denoting my father’s salary in the police department as a very small amount “plus loot” in his own inimitable style of describing the truth. The plea did the trick all right. On my part I recompensed him for his affectionate regard by taking pride in calling myself a ‘Biscoe boy’ and trying to deserve the name as it was a synonym for the brave and straightforward alumni of C.M.S School.”

Much later, in 1944, Biscoe wrote him a personal letter of encouragement and appreciation when he resigned from government service over a matter of principle. On his return from his near-drowning adventure in Djibouti, Biscoe invited him to a function at his house to meet the staff and senior students of the school to tell them of his experiences on the continent, as he was the first among the Biscoe boys to go overseas and return. “It was altogether a pleasant evening I spent with my friends of CMS and when I related the story about my drowning off the African coast they felt proud of the alma mater which taught us the art of swimming, paddling and social service in emergencies when danger to life was all too imminent”

Biscoe dedicated a life-time of service to the cause of education in Kashmir, spending the best part of 60 years in Srinagar. He uprooted himself reluctantly from the State in 1947, soon after India became independent, but only because he was advised that his presence might cause difficulties for the new Principal. He moved to Rhodesia, where he passed away eighteen months later at the age of 86. During his brief stay there, he worked on his autobiography and remained in touch with his trusted staff, offering them advice and encouragement. Each of his letters ended with the words, “My body is in Africa but my soul is in Kashmir” (H T-B: 2019:292). At the time of his departure, there were six CMS schools for boys and the first school for girls, the Mallinson School, which was started in 1912. [5] After 1947, at least four Chief Ministers and several government ministers and senior bureaucrats were alumni of the Biscoe school. The six schools underwent several upheavals and reversals of fortune in the decades that followed; at the present moment there is a functioning Biscoe School for boys and a Mallinson’s School for girls in Srinagar. It was my intention to visit the Biscoe School and see if it still adheres to, or has appropriately reinvented, some of the features that made it unique, but this visit will now have to wait for better times.

Reverend Tyndale-Biscoe’s record of converting Kashmiris to Christianity, as well his bosses at the Christian Mission Society might have wished, was not impressive, but he did succeed in mass conversions in the hearts and minds of the boys in his charge, by moulding them into well-rounded, strong and honest citizens, with a desire to help the weak, poor and oppressed – men and women, humans as well as animals - in effect converting them to his version of Christianity. TCW was one of these ‘Biscoe’ boys and this is the story of the school through his eyes. There must be countless others who were similarly influenced.

TCW never lost his boundless enthusiasm and affection for his alma mater and credited the school with shaping his character, instilling a long-lasting love of sports, and indeed making him the person that he was – upright, honest, imbued with a spirit of service and respect for all men and religions. His honesty was legendary, and it was said about him that he would not even accept a bouquet of flowers as a gift in his professional capacity. He believed in the power of education and was proud of his association with the Vasanta and Kashyapa High Schools for Girls that were run by the Women’s Welfare Trust in Srinagar. Given his impoverished family background, it would be no exaggeration to say that that had it not been for the education that he received in the school, and the support he received from Biscoe later, he might not have been in a position to pursue a university education, leading to an illustrious career in the civil service, where he rose to be the first Kashmiri head of a government department and was made Rai Bahadur for his services, a title that he returned to the State after India became independent. Tara Chand Wazir was his own man. His profound appreciation for Biscoe and his love for his alma mater did not prevent him from being anti-colonial in his intellectual and political stance. He was also deeply troubled by the proselytizing mission, though he did acknowledge that he had benefited from Biscoe’s sermons on the life of Christ, just as he did from his exposure to and study of other religions. He was a diehard supporter of Gandhi and Nehru, an admirer of Annie Besant and a member of the Theosophical Society.

Let me return to the beginning: TCW’s pithy remark about the ‘Biscoeism’ in his blood asserting itself off the coast of Djibouti,12 years after he had passed out of school, says it all. “Once a Biscoe boy, always a Biscoe boy” was a mantra that he repeated throughout his life.

[1] I have extracted my grandfather’s account of the incident, as well as of his years at the Biscoe School and the impact it had on him, from his unpublished memoirs (Wazir 1970).

[2] To illustrate his point, Biscoe (1920:75-6) provides the example of the father of one his students, who earns twenty rupees per month as a clerk in a government office. His office is 32 miles away, so he has to maintain two establishments, his own (costing nearly twenty rupees), and that of his family in Srinagar (also costing about the same). In addition, he employs two clerks to help him do his work at a salary of 7-8 rupees. These two clerks can also not survive on their pay alone, and so on.

[3] Fortunately, Biscoe wrote extensively about his experiences in Kashmir, leaving us with a rich source of background information, anecdotes, and insights into his unique methods as an educationist. His son Eric Tyndale-Biscoe, who worked at the school in various capacities, including as the Principal, has also written the story of the school. Most recently his grandson, Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe (2019), himself a student at the school, has added to this resource by bringing the narrative up to date, adding invaluable information from archival sources and providing a more nuanced, complex and personal perspective on the school that takes his grandfather’s name.

[4] Dunking children in the ice-cold waters of the Jhelum in mid-winter is probably a step too far but caning with stinging nettle was a standard punishment in certain institutions, even in the fifties and sixties when I was in school in Srinagar, though thankfully not in mine, and is perhaps still practiced.

[5] No doubt there is a story to be told about Muriel Mallinson and role of the Mallinson School for Girls in educating a generation of Kashmiri women who then went on to occupy prominent positions in Kashmir, but that is for someone else to narrate.

Khan, Mohammad Ishaq, (1978), History of Srinagar 1847-1947: A Study in Socio-Cultural Change, Srinagar, Aamir Publications.

Moorcroft, William & George Trebeck, Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Punjab, in Ladakh and Kashmir, 2 vols, London 1841.

Studdert-Kennedy, Gerald, 'Cecil Earle Tyndale-Biscoe' in H.C.G. Mathew and Brian Harrison ed. (2004), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, Vol. 5.

Temple, Richard (1887), Journals kept in Hyderabad, Kashmir, Sikkim and Nepal, vol. II., London: W.H. Allan & Co., edited by his son Richard Carnac Temple.

Tyndale-Biscoe, C.E., (1920), Character Building in Kashmir, London: Church Missionary Society.

Tyndale-Biscoe, C.E. (1925), Kashmir in Sunlight and Shade, London: Seeley, Service & Co. Limited.

Tyndale-Biscoe, C.E., (1951), Tyndale-Biscoe of Kashmir: An Autobiography, London: Seeley, Service & Co. Limited.

Tyndale-Biscoe, E.D. (1930), 50 Years Against the Stream: The Story of a School in Kashmir 1880-1930, Mysore, Wesleyan Mission Press.

Tyndale-Biscoe, Hugh (2019), The Missionary and the Maharajas: Cecil Tyndale-Biscoe and the Making of Modern Kashmir, London, I.B. Tauris.

Wazir,T.C, (1970), 'My Life Story, the Lessons it has Taught me – 77 Years in Retrospect', Unpublished.

and currently Senior Associate of

International Child Development Initiatives,

Leiden, The Netherlands.

She is the granddaughter of Tara Chand Wazir.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed