This article is reposted with permission from Sameer Arshad Khatlani's blog

The number of fatalities has been disputed but the data from the 1961 census – the first in J&K after 1947 – speaks for itself. As per the 1941 census, the Muslims accounted for 77.1 per cent of the state’s population excluding in areas that came under Pakistan’s control after 1947. Their population had gone down by almost 10 per cent and plummeted to 68.29 per cent in 1961,[3] confirming that tens of thousands of people were either killed or forced to flee to Pakistan.

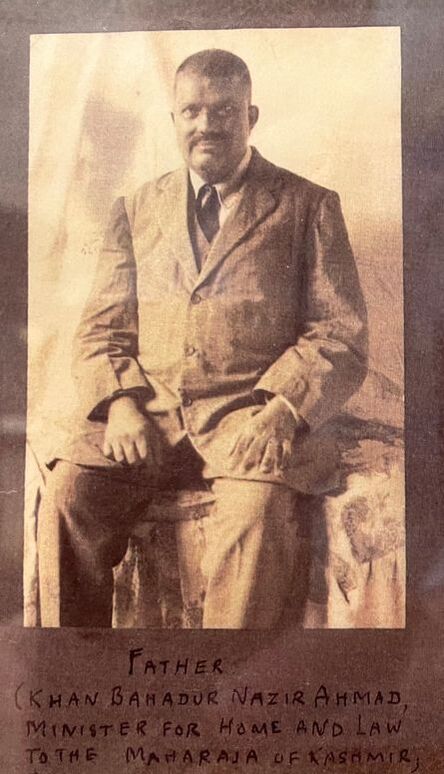

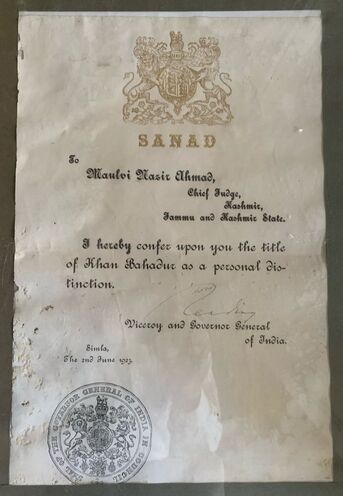

The trouble started brewing in Jammu city in August 1947 when departing British colonists ham-handedly divided the subcontinent into Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India. The division triggered deadly riots in neighbouring Punjab as the province’s eastern portion was emptied of Muslims and the western part (now Pakistan) of Hindus and Sikhs. The seizure of firearms from the Muslims in Jammu and their distribution among groups hostile to them portended the bloodbath that was to follow in the region. The handful Muslim police and revenue field officers were transferred as Muslim majority J&K’s ruler Maharaja Hari Singh allegedly turned a blind eye to attacks on Muslims and their properties. Hindu refugees, who had suffered violence and were driven out of newly-created Pakistan, carried tales of their sufferings and further ‘inflamed the situation’.[4] According to celebrated journalist Ved Bhasin, the violence started when some Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) men killed two Muslim police officers, Raja Iqbal Khan and Sheikh Imam Din.[5]

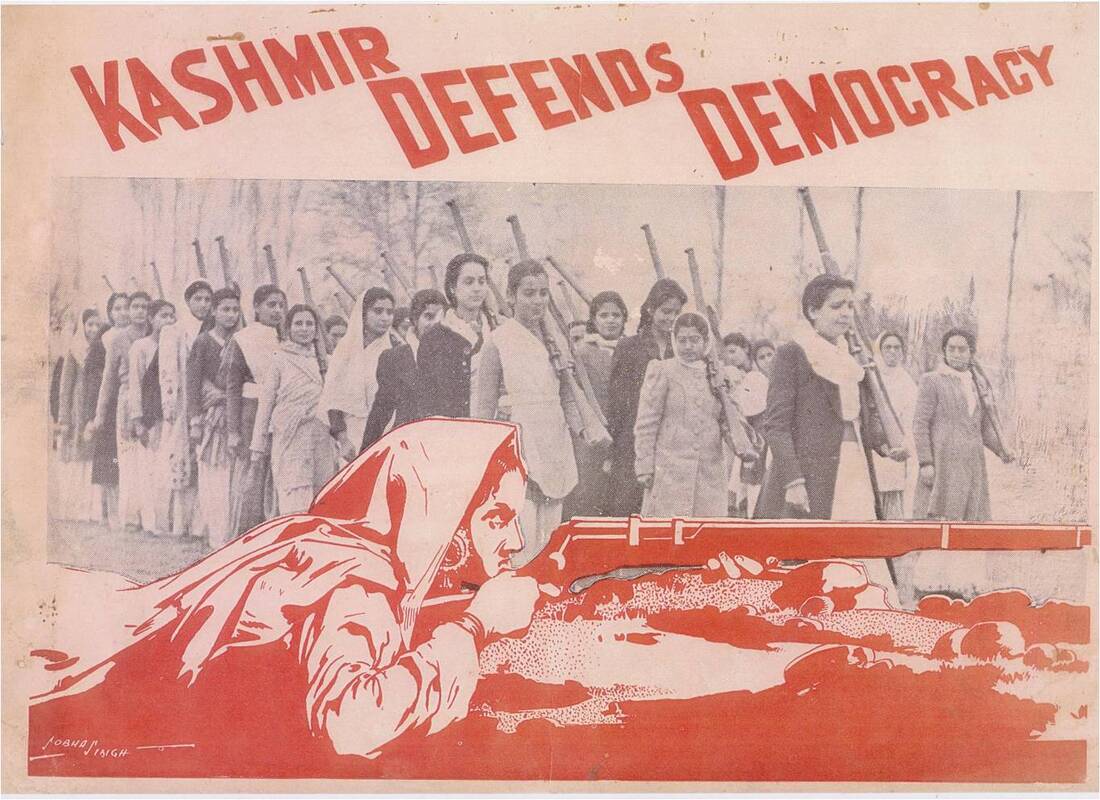

Many were lulled into believing that the initial violence in Jammu was another bout of communal rioting and would be contained.[6] Fat hit the fire soon when the harried Muslims found themselves with no escape route. Railway services from Jammu to Sialkot (now in Pakistan) were suspended and a permit system was introduced for traveling. The Muslims were left at the mercy of their attackers. By September end, they were besieged in Jammu city’s Muslim-majority localities of Talab Khatikan and Ustad Mohalla, where they were at the receiving end of intermittent small-arms fire [7] and were even denied water supply and food.[8] The encircled Muslims defended themselves with a handful of revolvers, rifles, swords, lances, daggers, hockey, sticks, and sticks. A retired British Indian Army officer, Captain Nasiruddin, taught the besieged residents defensive tactics and vigilance. A simple community meal was cooked daily. Members of the RSS and other hostile groups surrounded them and fired ceaselessly while refraining from an all-out attack. They were unsure about Muslim defensive capabilities; tactical steps taken thanks to Captain Nasiruddin had misled them. The capabilities were bolstered after some men broke into Major General Sumundar Khan’s house and found rifles with substantial ammunition. The rifles helped discourage a frontal attack.[9]

According to Bhasin, who was a 17-year-old student and peace activist in Jammu in 1947, ‘communal marauders’ brutally killed most of the Muslims outside the Muslim dominated areas. The marauders ‘moved freely in vehicles with arms and ammunition’ even when the city was under curfew’. In 2003, Bhasin, who was among those who managed to carry some food for besieged Muslim friends and others in Ustad Mohalla, recalled the curfew appeared to be meant ‘only to check the movement of Muslims’. Bhasin recalled that the Hindus had taken up positions on their houses before troops from Patiala joined them. In Billawar, stranded Muslims faced near starvation while women were abducted.[10]

British diplomat C B Duke, who visited the area in the third week of October, saw around 20 burnt out villages along the Chenab River and concluded that it was the Muslims ‘who were suffering’.[11] Tunzelmann writes that the Maharaja had ordered ‘ethnic cleansing under the guise of a defensive strategy’. [12] She notes that he meant to create an approximately three-mile wide buffer between his territory and Pakistan. ‘Muslims were either pushed into Pakistan, or killed.’ [13] In his painstakingly researched book Midnight’s Furies, Nisid Hajari writes that a ‘former but well-connected’ British intelligence operative provided the American embassy an ‘indisputably grim’ estimate. 'Sikhs and Hindus undertook a wholesale massacre of the local Muslims [in Jammu] and it is stated that up to 20,000 were killed at the end of October. This matter is … being kept strictly secret,' Hajari quotes the operative as saying.[14]

The estimate turned out to be a tip of the iceberg even as there is no consensus on the exact number of fatalities since the killings were never probed. On August 10, 1948, The Times estimated that 237,000 Muslims had disappeared from the eastern Jammu province. It said that they were ‘systematically exterminated – unless they escaped to Pakistan along the border – by all the forces of the Dogra state, headed by the Maharaja [Hari Singh] in person and aided by Hindus and Sikhs’. The Times concluded this ‘elimination of two-thirds of the Muslims last autumn has entirely changed the present composition of eastern Jammu province’.[15]

The situation worsened upon Hari Singh’s flight to Jammu city as Pakistan-backed fighters threatened to overrun his summer capital, Srinagar, in an attempt to capture J&K in late October 1947. Hari Singh is said to have fired at a roadside Muslim gathering on his way back ‘thus signalling to his Hindu subjects to follow suit’.[16] It marked the culmination of a sustained campaign of ‘harassment, arson, physical violence, and genocide’ against Muslims ‘in at least two areas – Poonch, right on the border with Pakistan, and pockets of southern Jammu’.[17] The Maharaja used brute force to quell an agitation against his direct takeover of Poonch and imposition of taxes. He asked the Muslims to surrender their arms and de-mobilised a large number of Muslim soldiers and police officers. The Muslims were particularly vulnerable in the region’s eastern parts, where they were outnumbered. They accounted for around 60 per cent of Jammu region’s 20 lakh population as per the 1941 census. In Jammu district, the Muslim proportion was around 40 per cent of the population [18], which was down to 7.02 per cent as per the latest census in 2011. [19] The Muslims constituted nearly 32 per cent of the population in Jammu city. [20] They were potential sitting ducks in the regions eastern parts as Hajari writes: ‘In addition to the incoming RSS fighters, thousands of revenge-minded Hindu and Sikh refugees from Pakistan had taken temporary residence in Jammu [city].’

By the last week of November when the damage was done, Nehru was forced to regret ‘heavy casualties' [21] Jammu Muslims had suffered even as he tried to keep the scale of the violence under wraps. He ensured the global attention remained focussed on the tribal fighters as part of his efforts to ensure that the Muslim-majority state acceded to India and not Pakistan. India consequently ‘chose not to publicise’[22] the fresh violence in Jammu region in November 1947. It succeeded and how: Seven decades later, not many even in J&K know about the nature of the violence and its perpetrators. Tunzelmann writes India would deny that ‘any holocaust had taken place, perhaps because it was secretly providing arms to the Dogra [Hari Singh]’s side’.[23] Hajari concludes that Nehru was being ‘cavalier’ and should ‘have known better’[24] the situation in Jammu. His envoy, Dalip Singh, had warned Nehru from Jammu that cadres of RSS, the parent organisation of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), had been infiltrating into the region. Singh, a former high court judge, cautioned Nehru that the infiltration was happening with ‘help of elements in the Indian Army’. ‘Almost every official is secretly in sympathy with them [RSS] and would probably turn a blind eye on their entry,’ Singh wrote to Nehru. Hajari writes that the Hindu extremists were hitching rides on army trucks amid rumours that Hari Singh was using them as ‘shock troops to rid Jammu of its Muslims’.[25] In an October 2012 document titled ‘vision and mission’, the RSS acknowledged the ‘timely collaboration of the entire Sangh (RSS) force then present at Jammu with the Armed Forces of Bharat [India]’ in 1947.[26]

Hari Singh shared close ties with the RSS, which was formed in the 1930s. He gave up on his insistence on remaining independent and agreed to accede to India after Nehru’s Hindu traditionalist deputy, Vallabhbhai Patel, sought RSS chief M S Golwalkar’s help in convincing the Maharaja in October 1947.[27] Hari Singh revered Golwalkar, who headed the RSS in the 1940s and approved of Germany’s ‘purging the country of the Semitic Races — the Jews’ and urged Hindus to replicate a similar ‘Race Spirit’ with Muslims.[28] He ‘bowed his head’ in front of Golwalkar and had a change of heart after his meeting in Srinagar with the RSS chief. Hari Singh had till then ‘remained unmoved by many national leaders’[29], including India’s supreme leader Gandhi and rebuffed their attempts to woo him. He had met Gandhi two months earlier when Hari Singh believed Kashmir could remain independent’.[30]

Golwalkar achieved what his arch-rival, Gandhi, could not. Hari Singh agreed to send the accession proposal to India upon meeting Golwalkar after understanding ‘the importance of protection of his religion’. RSS volunteer M G Chitkara writes Patel knew Hari Singh’s mind as the Maharaja was ‘in a terrible fix’ unable to come to any decision with ‘many apprehensions’ about joining India. He adds Patel gauged Golwalkar was the right person ‘endowed with the necessary skill and commanding the implicit confidence of both Patel and the Maharaja’ to convince him. Hari Singh told Golwalkar that his state was fully dependent on Pakistan with all surface routes passing though Sialkot and Rawalpindi. ‘Lahore is my airport. How can I have relations with India?’ Hari Singh asked. Golwalkar brought up the emotive issue of Hari Singh being ‘a Hindu king’ and explained to him ‘your Hindu people’ would struggle ‘against grave difficulties’ if he acceded to Pakistan. The RSS chief talked him out of his idea of retaining an independent kingdom, saying it was a futile idea as Pakistan ‘would never tolerate it’ and engineer internal Muslim revolt.[31]

It was perhaps no coincidence that violence in Jammu escalated after the meeting. Hajari writes that Hari Singh’s troops piled an estimated 5,000 men, women and children into buses on the pretext of taking them to Pakistan on November 5 and 6. Instead, they were taken somewhere else where ‘most likely Akali and RSS extremists’ sprayed them with bullets. Hajari writes a ‘couple hundred Muslims escaped into fields’ while the rest were either raped or killed outright’.[32] One of the escapees, former civil servant Tariq Masud, corroborates Hajari’s account. Masud’s family was vacationing in Kashmir’s resort town of Pahalgam when the trouble started in their native Jammu city. They made a potentially fatal decision to return home in mid-September before deciding to send women and children to Gujrat, roughly 100km away in Pakistan, as the situation worsened. But they remained stranded in Jammu with an escalation in the violence. Masud remembers seeing smoke rising from adjoining hills as arson, looting, and killing of Muslims around Jammu increased. His father managed to get a permit for the family to travel by horse cart to Suchetgarh border with Pakistan. Raja Sohbat Ali, a police officer friend, dissuaded him from travelling without an escort citing attacks on Muslim evacuees. He promised to escort them to the border the following day. But Ali could not keep him promise. Masud writes RSS volunteers ‘ruthlessly killed’[33] Ali by pumping bullets point-blank in his chest; his two fingers with gold rings on them were chopped off.

By September end, Masud’s family was forced to join other Muslim survivors in the city’s Muslim-majority area. Masud writes that ‘Hindu elements’ had organised themselves and ‘virtually encircled the Muslim sanctuary’, where his father and another doctor established a first-aid centre after breaking into a closed chemist shop. He adds the brutalities against Muslims ‘increased manifold’ after Hari Singh’s arrival in Jammu as ‘houses were burnt, property plundered, women molested and taken away and men killed or maimed’. Masud writes tensions peaked as the RSS reportedly vowed Muslim men and women would be sacrificed on Eid that year instead of sheep and goats. A week-long lull followed before announcements were made asking Muslims to assemble in Jammu’s Police Lines on November 5, 1947, if they wished to go to Pakistan. Each family was instructed to carry a suitcase and one set of beddings with the promise that their belongings would be transported later.[34]

Masud estimates around 5-6,000 Muslims gathered for their evacuation on the first day but there were ‘too few’ buses ‘to carry even 20 per cent of the assembly’. The harried people were desperate to travel as soon as possible. Masud’s whole clan managed to travel as part of the first convoy, comprising 30-35 small buses with the capacity of over a dozen passengers each. About 25-30 women and children were stuffed inside a bus while 15-16 men sat on the roofs of the buses. Masud recalls drivers and cleaners of the buses wielded swords and were accompanied by Hari Singh’s soldiers. Two army vehicles escorted their convoy of buses packed like sardines. The evacuees were more uncomfortable with their army escorts whom they did not trust. Their worst fears came true when the buses turned east on a dirt road toward Kathua instead of proceeding to Sialkot through a metalled road. Sensing trouble, women and kids started wailing and praying as mobs carrying swords and lances moved freely. One bus broke down near Samba, but the convoy did not stop, leaving the passengers at the mercy of the armed mobs. An hour later, a mob began attacking and looting the evacuees when the convoy halted at Mawa, a village between Samba and Kathua. A soldier in charge of the convoy had allowed an estimated 1,000-1,200 evacuees alight from the buses and sit in a field there as he awaited further orders while armed locals hovered around.

Mawa happened to be just three kilometres from the border. Masud’s uncle, Fazal-e-Haq, a customs department official, happened to be familiar with the area having extensively toured it a few years earlier. He was confident of finding their way as he planned to first slip away along with an elderly family member while Masud’s another uncle had gone missing. An hour later, the mob started attacking and looting the convoy. Masud writes that luckily for them, the attackers’ first priority appeared to be looting and taking away women. Uniformed armed guards joined the loot, giving them precious 15-20 minutes to sprint westwards to save their lives. The caravan split up amid desperate cries for help and rifle shots. Some evacuees fell into pits of nearby brick-kilns and many were mercilessly killed. [35]

Masud’s group of 70-75 people did not know the route to Pakistan but continued trotting westwards. They avoided getting close to villages or speaking loudly. Cries of kids, including Masud’s infant brother, Arif Kamal, prompted angry responses from the caravan leaders who would ask mothers to smother them. Dogs barked at them fanatically at several places forcing them to retreat. Masud writes their total belongings included Kamal’s bag containing a milk bottle, a tin of milk powder and a brush. He had lost his shoes at Mawa and hopped barefooted all the way with paperback books from their library stuffed in his pockets. Other children in the caravan were aged between 13 and one-month-old as it trudged for hours. None of them had eaten since their breakfast on November 5. In the early hours of November 6, 1947, the caravan crossed a small stream and met a man dressed in typical Punjabi attire. He told them what they were dying to hear: ‘You are already about two miles inside Pakistan, this is village Chang and I am Alaf Din’. [36] Masud’s family was lucky to be reunited with their other relatives at a refugee camp in Pakistan. Fazal-e-Haq had easily crossed over thanks to his knowledge of the terrain. The missing uncle had stayed back with a Hindu friend and safely managed to reach Gujrat after remaining in hiding for weeks.

A convoy of trucks Hari Singh’s government had arranged and his troops escorted met the same fate. The convoy carrying around 1,200 evacuees was stopped outside Jammu city as the troops ordered them to disembark. Armed men emerged from behind trees and started hacking, slashing and smashing the civilians. In 2017, Mazhar Malik, 86, who lost his father in the violence, cited the account of a survivor and told The Guardian:

old people fell silently to their knees; men tried in vain to fight back.

Mercifully, because it was dark by then, about one-third succeeded in escaping.

The border was just a few miles away and the lucky ones managed to straggle across.

Our father was not one of them. [37]

Bhasin squarely blamed Hari Singh for the carnage. According to him, instead of trying to prevent killings and ensuring peace, ‘the Maharaja’s administration helped and even armed the communal marauders’. Clearly, for him, it was a ‘planned genocide by the RSS activists who were joined by Sikh refugees from West Pakistan and enjoyed full protection and patronage of the administration’.[38] Bhasin insisted that the administration was involved in changing Jammu’s demographic character. Jammu governor Lala Chet Ram Chopra summoned Bhasin and warned him of consequences for his Students Union’s peace efforts. Chopra told Bhasin that they were imparting arms training to Hindu and Sikh boys in Rehari area and asked him and his colleagues to join it. A colleague of Bhasin found that soldiers were training some RSS youths and others in using 3.3 rifles when he sent him to the training camp the next day. In 2003, Bhasin recalled Hari Singh’s Prime Minister Mehr Chand Mahajan asking a delegation of Hindus to demand parity with the transfer of power from the Maharaja. He pointed to Ramnagar Rakh, where some bodies of Muslims were still lying, and said that the population ratio too can change when asked how they could demand parity amid difference in the population ratio.

According to Bhasin, Ramnagar Rakh was ‘littered with the dead bodies of [Muslim] Gujjar men, women, and children. A colleague of Bhasin rescued a young girl crying near the bodies of her parents in Ramnagar. [39]

Nehru found ‘a great deal of trickery and very probable connivance’ by Hari Singh’s troops in the massacre but did nothing.[40] He lauded ‘remarkable communal unity’ in Kashmir Valley where people demonstrated ‘cohesion of purpose and effort in the face of common danger’.[41] Nehru had around a fortnight earlier visited Kashmir, where he was delighted to see the order Kashmir’s popular leader Sheikh Abdullah’s pro-India National Conference militia had restored. Kashmir presented a contrast to the bloodbath in Delhi, Punjab, and Jammu triggered by the hurried division of India. He lauded a gathering in Srinagar, saying that they had not only saved Kashmir but also restored India’s prestige. For Nehru, the inter-community harmony in Kashmir had brought hope to his disappointed heart. He declared Kashmir had set an example for the whole of India.[42] Gandhi, too, held Hari Singh responsible including for ‘the murders of numberless Muslims and abduction of Muslim girls in Jammu’. [43] He recognised Abdullah’s efforts in protecting non-Muslims in Kashmir and contrasted his commitment to secularism with attacks on Jammu Muslims. Gandhi famously described Kashmir, where Sheikh Abdullah promptly acted to protect Hindus and Sikhs by ordering his volunteers to protect them,[44] as a ‘ray of hope’. [45]

Khatlani has reported from Iraq and Pakistan and covered elections and national disasters. He received a master’s degree in History from the prestigious Jamia Millia Islamia University in New Delhi. Khatlani is a fellow with Hawaii-based American East-West Center established by the US Congress in 1960 to promote better relations and understanding with Asian, and Pacific countries through cooperative study, research, and dialogue.

Penguin published Khatlani’s first book The Other Side of the Divide: A Journey into the Heart of Pakistan in February 2020. The eminent academic and King’s College professor, Christophe Jaffrelot, has called the book ‘an erudite historical account... [that] offers a comprehensive portrait of Pakistan, including the role of the army and religion—not only Islam’.

[2] Alex Von Tunzelmann, Indian Summer: The Secret History of The End Of An Empire, London: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 287

[3] Asghar Ali Engineer, Communal Riots in Post-Independence India, Hyderabad: Sangam Books, 1997, p.157

[4] Tariq Masud, Escape from Paradise, November 13, 2015, The Friday Times, http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/escape-from-paradise/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[5] Ved Bhasin, Jammu 1947, November 17, 2015, The Kashmir Life, http://kashmirlife.net/jammu-1947-issue-35-vol-07-89728/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[6] Moni Mohsin,‘The wounds have never healed’: living through the terror of partition, August 2, 2017, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/02/wounds-have-never-healed-living-through-terror-partition-india-pakistan-1947, accessed on June 29, 2019

[7] Tariq Masud, Escape from Paradise, November 13, 2015, The Friday Times, http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/escape-from-paradise/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[8] Bhasin, Jammu 1947, November 17, 2015, The Kashmir Life, http://kashmirlife.net/jammu-1947-issue-35-vol-07-89728/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[9] Tariq Masud, Escape from Paradise, November 13, 2015, The Friday Times, http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/escape-from-paradise/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[10] Ved Bhasin, Jammu 1947, November 17, 2015, The Kashmir Life, http://kashmirlife.net/jammu-1947-issue-35-vol-07-89728/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[11] Alex Von Tunzelmann, Indian Summer: The Secret History of The End Of An Empire, London: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 287

[12] Alex Von Tunzelmann, Indian Summer: The Secret History of The End Of An Empire, London: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 287

[13] Alex Von Tunzelmann, Indian Summer: The Secret History of The End Of An Empire, London: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 287

[14] Nisid Hajari, Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition, Gurgaon: Viking, 2015, p. 209

[15] Christopher Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History, Noida: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2013, p. 55

[16] Tariq Masud, Escape from Paradise, November 13, 2015, The Friday Times, http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/escape-from-paradise/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[17] Alex Von Tunzelmann, Indian Summer: The Secret History of The End Of An Empire, London: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 286

[18] Ved Bhasin, Jammu 1947, November 17, 2015, The Kashmir Life, http://kashmirlife.net/jammu-1947-issue-35-vol-07-89728/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[19] Zeeshan Shaikh, Share of Muslims and Hindus in J&K population same in 1961, 2011 Censuses, December 30, 2016, The Indian Express,http://indianexpress.com/article/explained/share-of-muslims-and-hindus-in-jk-population-same-in-1961-2011-censuses/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[20] Ved Bhasin, Jammu 1947, November 17, 2015, The Kashmir Life, http://kashmirlife.net/jammu-1947-issue-35-vol-07-89728/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[21] Christopher Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History, Noida: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2013, p. 73

[22] Christopher Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History, Noida: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2013, p. 73

[23] Alex Von Tunzelmann, Indian Summer: The Secret History of The End Of An Empire, London: Simon & Schuster, 2007, p. 287

[24] Nisid Hajari, Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition, Gurgaon: Viking, 2015, p. 208

[25] Nisid Hajari, Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition, Gurgaon: Viking, 2015, p. 208

[26] Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Vision and Mission, rss.org, October 22, 2012, http://rss.org/Encyc/2012/10/22/rss-vision-and-mission.html, accessed on June 29, 2019

[27] M. G. Chitkara, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: National Upsurge, New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation, 2004, p. 263

[28] Siddhartha Deb, Unmasking Modi, May 3, 2016, The New Republic, https://newrepublic.com/article/133014/new-face-india-anti-gandhi, accessed on June 29, 2019

[29] M. G. Chitkara, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: National Upsurge, New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation, 2004, p. 263

[30] Nisid Hajari, Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition, Gurgaon: Viking, 2015, p.180

[31] M. G. Chitkara, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: National Upsurge, New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation, 2004, p. 263

[32] Nisid Hajari, Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition, Gurgaon: Viking, 2015, p. 209

[33] Tariq Masud, Escape from Paradise, November 13, 2015, The Friday Times, http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/escape-from-paradise/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[34] Tariq Masud, Escape from Paradise, November 13, 2015, The Friday Times, http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/escape-from-paradise/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[35] Tariq Masud, Escape from Paradise, November 13, 2015, The Friday Times, http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/escape-from-paradise/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[36] Tariq Masud, Escape from Paradise, November 13, 2015, The Friday Times, http://www.thefridaytimes.com/tft/escape-from-paradise/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[37] Moni Mohsin,‘The wounds have never healed’: living through the terror of partition, August 2, 2017, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/02/wounds-have-never-healed-living-through-terror-partition-india-pakistan-1947, accessed on June 29, 2019

[38] Ved Bhasin, Jammu 1947, November 17, 2015, The Kashmir Life, http://kashmirlife.net/jammu-1947-issue-35-vol-07-89728/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[39] Ved Bhasin, Jammu 1947, November 17, 2015, The Kashmir Life, http://kashmirlife.net/jammu-1947-issue-35-vol-07-89728/ accessed on June 29, 2019

[40] Nisid Hajari, Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition, Gurgaon: Viking, 2015, p.210

[41] Christopher Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History, Noida: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2013, p. 73

[42] Nisid Hajari, Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition, Gurgaon: Viking, 2015, p.10

[43] Christopher Snedden, Kashmir: The Unwritten History, Noida: HarperCollins Publishers India, 2013P 73,

[44] Ajit Bhattacharjea, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah: Tragic Hero of Kashmir, New Delhi: Lotus, p. xxiv, xxvi

[45] Ajit Bhattacharjea, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah: Tragic Hero of Kashmir, New Delhi: Lotus, p. xxiv, xxvi

RSS Feed

RSS Feed